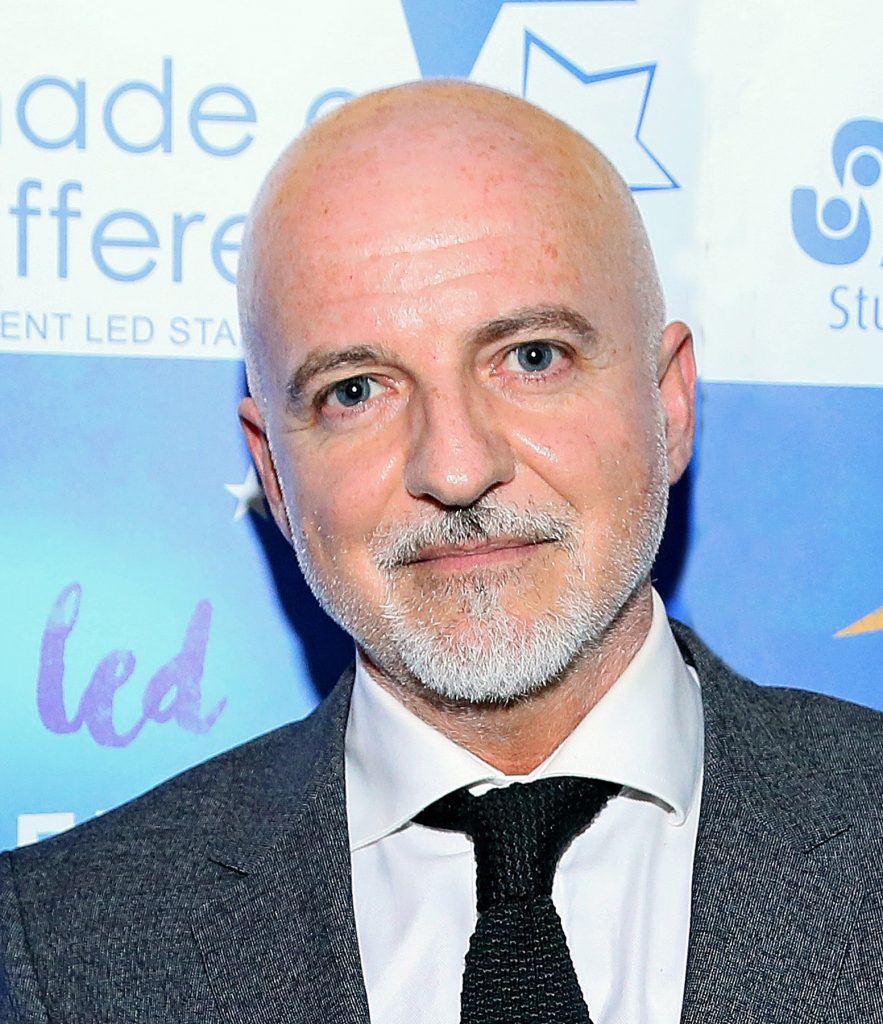

Welcome to our series in which we ask researchers to tell us how their research is of use and relevance for the classroom. Today, we are delighted to welcome Roberto Filippi, Associate Professor at UCL Institute of Education.

Welcome to our series in which we ask researchers to tell us how their research is of use and relevance for the classroom. Today, we are delighted to welcome Roberto Filippi, Associate Professor at UCL Institute of Education.

What is the focus of your research?

My area of research is second language acquisition with specific focus on the effects of bilingualism (or multilingualism) on cognitive development across the lifespan. This has become a very hot topic in recent years, mostly due to the increased multiculturalism in our societies. According to some reliable estimates, more than half of the world’s population is fluent in two or more languages – more than three billion people! We can safely say that bilingualism is not an exception and studying multilingual speakers offers a unique opportunity to understand how language develops and what its interactions are with the rest of the cognitive system.

What led you to this area of research?

Being the father of two bilingual children, I can’t deny that I have a strong personal interest. I began studying bilingual children more than 10 years ago in a London primary school in which the large majority of children were bilinguals. I directly experienced the challenges that teachers face everyday, but also the advantages that a multicultural / multilinguistic community can offer. Building a bridge between science and education was a very rewarding experience, an experience that I wish to continue even more here at the UCL Institute of Education.

Could you summarise your findings?

A decade of research in this area has shown many positive effects of second language development. I should say that studying bilingual / multilingual speakers is not an easy task. Second language learning occurs everyday and defining someone as “bilingual” does not explain the complexities of this phenomenon. Nonetheless, our studies try to take into account the many variables that might affect our findings like, for example, our participants’ linguistic experience, age of second language acquisition/exposure, levels of proficiency in both languages and socio-economic status.

Our studies have shown that bilingual children who learnt two languages from birth and bilingual adults who started to learn a second language much later in life, enjoy the remarkable ability to filter out sound interference when attending to a task – in our case the comprehension of speech. A possible interpretation of these finding is that bilinguals have to deal with two languages in a single mind. They need to filter out interference from the non-target language (i.e., the language that is not in use) and activate that target one (i.e., the language that one wants to speak or listen to). As a result of this intense and daily “brain training”, bilinguals may develop a stronger resilience than monolingual speakers to environmental distractions. Remarkably, in another study in which we used modern neuroimaging techniques, we found that the ability to control verbal interference in bilinguals is associated with a specific area of the cerebellum. This may indicate that the bilingual brain has a different functional and structural development compared to the monolingual brain, even in areas that were largely unexplored, such as the cerebellum.

What do you think this means for teachers in the classroom?

We are continuously bombarded by visual and auditory stimuli that affect our concentration. Our attention skills are very limited and prone to distractions that may impair our performance in everything we do. Classrooms are very noisy environments in which children need to learn in the presence of many environmental distractors. If our studies confirm that acquiring two (or more) languages early in life may enrich a capacity for filtering out distractors and learning more efficiently, I think we will offer educators and policy makers additional scientific evidence that multilanguage acquisition is beneficial for cognitive development.

If you could give one tip to teachers based on your work, what would it be?

Never discourage parents from raising their children in multilingual environments. Unfortunately, there are still cases in which educators advise multilingual families to raise their children as monolingual, to avoid “mental confusion”. This advice comes from early research showing that bilingualism was detrimental for a child’s cognitive development. However, this research has proven to be flawed. Decades of more rigorous and controlled scientific studies have not supported this view at all: there is no evidence that second language acquisition can impair development.

Therefore, I think it is the responsibility of the scientific community to provide research-based evidence and actively engage with education professionals. We need to work together to give our children everything they need.