At the Centre for Educational Neuroscience, we are interested in finding practical solutions for impediments to bringing research and education together. Those with a foot in both camps are often key to providing insights into these solutions.

Teacher turned researcher Michael Hobbiss writes a guest blog for us about what he believes are some of the difficulties facing evidence-based education and suggests a solution which may help, as he calls it, ‘teachers get more skin in the game’…..

A frequently expressed ambition in evidence-based education circles is that teachers can be trained (or encouraged… or forced) to be ‘critical consumers’ of research evidence. This aim encompasses two imagined steps: that teachers should read more research evidence in the first place, and then that they should also have the skills to appraise each piece of evidence’s potential to positively impact their own practice. Four years ago, before I left teaching to start my PhD, I expressed these ambitions myself, and subjected my long-suffering colleagues to training sessions designed to encourage similar enthusiasm in them. Now, having seen the other side of academic research, I’m not so sure that this is the right approach. I think that to cast teachers as merely ‘consumers’ of research, however ‘critical’, is to unfairly place them at the bottom of a food chain that does not exist; the bottom-feeders hoovering up the morsels drifting down from the academic heights. This not only does teachers a disservice, but actually more importantly it leads to research which is less impactful, less relevant to schools, and ultimately, less useful.

Indeed, the mere fact that this ‘critical consumers’ aim exists is hugely revealing about the state of much educational research, as it shows that as things stand, it doesn’t really matter all that much whether teachers read the research or not. That simply isn’t the metric by which it will be judged. The reward structures of academic research and funding mean that citations from other researchers, and publications in particular journals, are far more valuable to an academic than positively impacting the practice of teachers. This is not to dismiss the use of educational research, nor to question the desire of many academics to make a difference in the real world, merely to observe that the system is not currently structured to facilitate this process. The phrase ‘skin in the game’ re-popularised recently by the book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb describes how decisions are impacted by the level of involvement a person has with the project. The more ‘skin’ (personal involvement) you have in the game, the more you are likely to work towards ends that are personally beneficial. Currently, in educational research, teachers have no skin in the game. They are expected to invest nothing into the research process, and as a result, they receive no influence over its structure or direction.

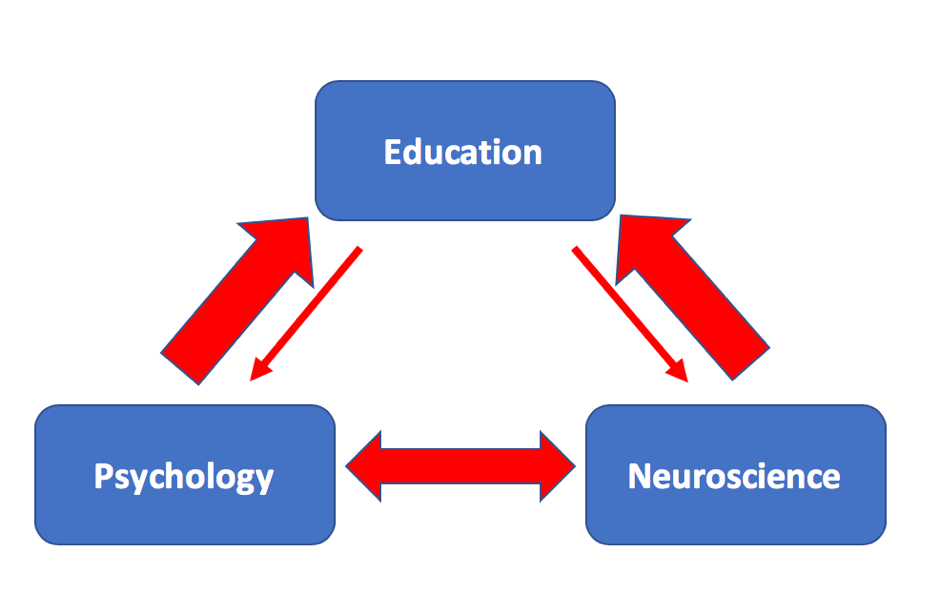

Figure 1: Without ‘skin in the game’, teachers have very little influence over the research process. They are expected to ‘consume’ research, even when it may not be directly relevant for them

Two common examples of ‘educational’ research which reflects this imbalance of incentives are:

- Outcome measures are of rarely of direct relevance to teachers. Educational interventions will often use outcome measures which are research-relevant (such as performance on lab experiments, working memory tests, or academic questionnaire measures) rather than ones that are directly applicable to teachers (such as test scores). Teachers are left to guess whether “improved inhibition and task-switching” (for example) means that Johnny is likely to do better in his Science test next week.

- Research questions are often theory-focused, as opposed to practice-focused. Building on the first point, frequently the hypotheses investigated by ‘educational’ research are ones that are not really designed to be useful to teachers at all. I frequently see research described as ‘educational’, when actually the questions are more developmental (e.g. ‘how does algebraic understanding develop across adolescence?’). A research question that was practice-focused and immediately applicable might be more useful, such as ‘What is the best approach for delivering the new AQA GCSE Maths course?’.

One of the consequences of having skin in the game is increased risk-aversion. As things stand, researchers are less likely to adopt more practice-focused research questions and outcome measures, which are far riskier under current incentive systems that often do not reward them. So nothing changes.

Getting teachers in the game

There is clearly no quick, simple fix to these problems. They are structural, deep and can only be changed with small steps and great patience. I do think though, that one fundamental solution to this problem is relatively simple: teachers need some skin in the research game too. If teachers, as a part of their ongoing professional development, were expected to take more of a part in the creation (rather than simply the consumption) of research, then both sides would stand to benefit. Clearly educators would benefit from being able to push for research questions and measurements which were more directly grounded in the everyday experiences and needs of educators. Although it might seem like a risk initially, researchers would also stand to benefit, as being able to demonstrate direct influence on real-world impact of research is (slowly) being increasingly incorporated into academic evaluations such as the (Research Excellence Framework) and grant funding criteria (through demonstrating Patient and Public Involvement, for example). Another huge potential benefit for researchers is recruitment. If we can provide more incentive for schools to take part in research in the first place (for example by having the chance to actively contribute to the process), then they are far more likely to want to participate in it, easing one of the most tiresome chores of the educational researcher: school recruitment.

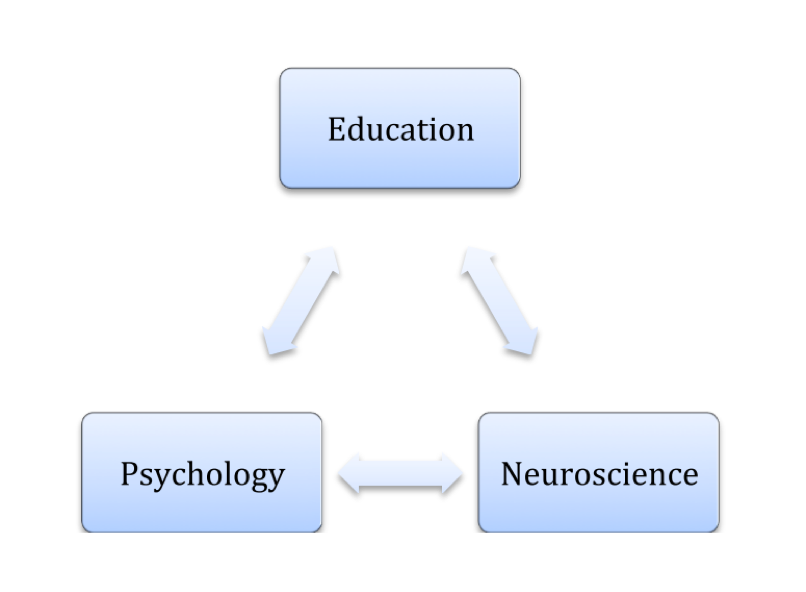

Figure 2: The idealised picture of knowledge exchange in a ‘transdisciplinary’ science of learning. Taken from Tokuhama-Espinosa (2010)

A ‘Craigslist’ for Schools and Researchers

So how do get teachers in the game? Simply, we need to talk. We need to talk early, we need to talk often, and we need to talk better. Currently, most contact between researchers and schools happens relatively late in the research process, well after hypotheses and methodology have been decided upon. Teachers are therefore disenfranchised from the research process, and from shaping it to their own benefit. Along with a number of colleagues (including both teachers and researchers) I have recently been working on a system designed to facilitate communication at a much earlier stage, roughly based on the design of the ‘Craigslist’ website (‘Gumtree’ might be the most familiar example of a similar system in the UK). Teachers and researchers can specify their areas of interest using themed ‘tags’, and will then be able to search for and view other members with similar mutual interests to them. In so doing, contacts can be made between researchers and schools with shared priorities far earlier, and far more efficiently, than is currently the case. Schools and teachers will then be in a position to exert far more influence over the subsequent development of the project. They’ll have some skin in the game. Whilst not a silver bullet, we hope that such a platform might at least start to provide the foundation for a much more equal, ‘transdisciplinary’ field than is currently the case.

We hope to publish an article on this project by early summer, along with a working prototype of the platform for road testing. In the meantime, it would be great to hear from any teachers or researchers who are keen to be updated on the further development of the system, or who have any suggestions for its development. michael.hobbiss@gmail.com

Click here to read more from Mike