The CEN has published a new paper! It presents the pilot study carried out at the start of UnLocke, a multidisciplinary and collaborative research project aiming at better understanding how primary school children learn counterintuitive concepts in maths and science. In this blog Dr. Hannah Wilkinson, postdoctoral researcher at Birkbeck University, summarises the paper and its key implications.

The CEN has published a new paper! It presents the pilot study carried out at the start of UnLocke, a multidisciplinary and collaborative research project aiming at better understanding how primary school children learn counterintuitive concepts in maths and science. In this blog Dr. Hannah Wilkinson, postdoctoral researcher at Birkbeck University, summarises the paper and its key implications.

Why did you carry out this study?

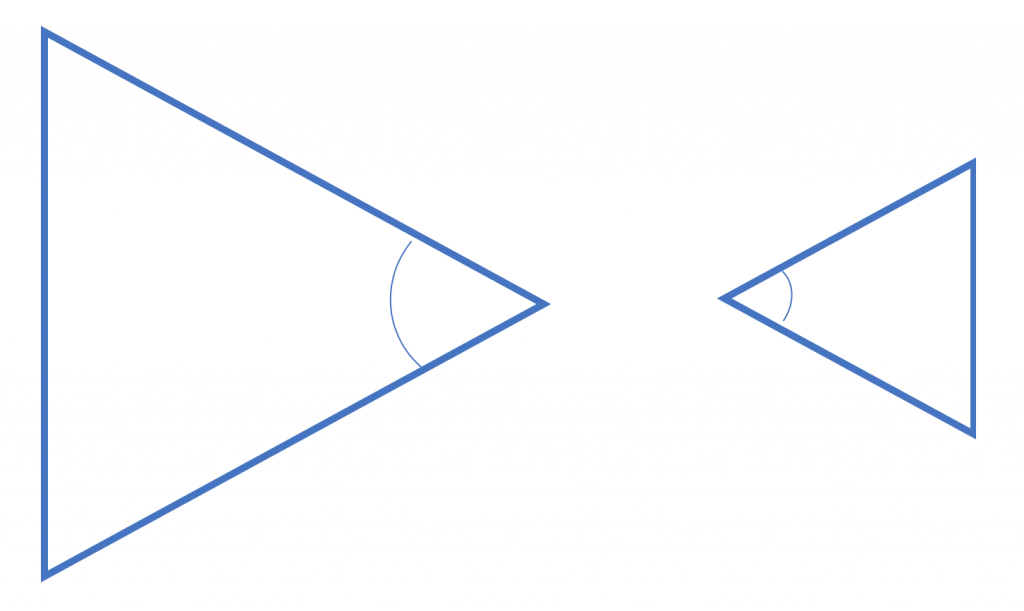

Many concepts in maths and science are counterintuitive [1]. This is because children hold naïve theories based on their first-hand experiences of the world (e.g. a belief that the world is flat as the ground beneath us appears flat and when a child kicks a ball it behaves as if on a flat surface) or misleading perceptual cues (e.g. a belief that the angles in a large triangle are greater than those in a small triangle, because the overall shape is larger). These ‘misconceptions’ can interfere with learning new concepts, even into adulthood [2].

Evidence from cognitive neuroscience suggests that learning counterintuitive concepts requires inhibitory control [3,4]. Inhibitory control is the ability to withhold an intuitive, pre-potent response, in favour of a more considered response – it is one of a set of cognitive control processes or ‘executive functions’ [5]. Therefore, we were interested in finding out whether training children to use their inhibitory control could improve learning of counterintuitive concepts. However, traditional executive function training has shown limited success in terms of participants transferring their skills beyond the trained task [6]. Taking a novel approach, we developed and evaluated a computerised classroom-based intervention, Stop & Think, which embeds inhibitory control training within the specific domain in which we would like children to use it, i.e. content from the maths and science school curricula.

What are your key findings?

Cross-sectional analyses of data from 627 children in Years 3 and 5 (7- to 10-year-olds) demonstrated that inhibitory control (measured on a Stroop-like task) was associated with counterintuitive reasoning and maths and science achievement.

In addition, a subsample of 456 children had teaching as usual or participated in Stop & Think (12 minutes, 3 times per week) for 10 weeks. There were no significant intervention effects for Year 5 children. However, for Year 3 children, Stop & Think led to significantly better maths and science counterintuitive reasoning performance and significantly better standardised science achievement scores (but not maths achievement scores) compared to teaching as usual.

Why is it important for educators?

These findings support the idea that inhibitory control contributes to counterintuitive reasoning and mathematics and science achievement. Therefore, ensuring children can effectively use their inhibitory control in the classroom is important for educators.

From an educational neuroscience perspective, these findings provide preliminary evidence that a neurobiologically-informed intervention delivered by teachers in the classroom, can improve ‘real-world’ academic learning.

Furthermore, there have been few interventions that target primary school science despite the subject’s economic importance [7]. Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) industries contribute over £68 billion a year to the UK economy and account for over a third of UK exports. Despite their importance, there has been little emphasis on interventions that target mathematics and science skills, particularly when compared to the wealth of literature on literacy skills intervention. The promising findings here, in particular for Year 3 science, suggests that there could be educational and economic gains from training such as Stop & Think as an educational tool within primary school lessons.

Additional resources

> You can read the full paper here.

> The Unlocke website gives some more information about the Stop & Think intervention, and about the multiple steps of the Unlocke project.

> In this blog post, Iroise Dumontheil shares the results of a larger-scale intervention with Stop & Think.

> “Overcoming students’ misconceptions”, an article for the BOLD blog by Dr. Annie Brookman-Byrne.

References

[1] Allen, M. (2014). Misconceptions in primary science. McGraw-hill education (UK).

[2] McNeil, N. M., & Alibali, M. W. (2005). Why won’t you change your mind? Knowledge of operational patterns hinders learning and performance on equations. Child Development, 76(4), 883–899.

[3] Mareschal, D. (2016). The neuroscience of conceptual learning in science and mathematics. Current Opinion in Behavioural Sciences, 10, 14–18.

[4] Vosniadou, S., Pnevmatikos, D., & Makris, N. (2018). The role of executive function in the construction and employment of scientific and mathematical concepts that require conceptual change learning. Neuroeducation, 5(2), 62–72.

[5] Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168.

[6] Diamond, A., & Ling, D. S. (2016). Conclusions about interventions, programs, and approaches for improving executive functions that appear justified and those that, despite much hype, do not. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 18, 34–48.

[7] Morse, A. (2018). Delivering STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) skills for the economy. National Audit Office.

Prof. Chloë Marshall led a discussion of two papers recently published by Laurence Leonard and his colleagues in the Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. They investigated some of the factors that can enhance word learning in children with developmental language disorder (DLD).

Prof. Chloë Marshall led a discussion of two papers recently published by Laurence Leonard and his colleagues in the Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. They investigated some of the factors that can enhance word learning in children with developmental language disorder (DLD).