The brain has a layered structure. You can think of it a bit like the layers of the Earth, from the crust, to the mantle, down to the burning, ancient core.

The outer layers of the brain process information without caring too much about goals or emotions. Some call it ‘cold cognition’. The inner layers increasingly process information in terms of goals and emotions, so-called ‘hot cognition’.

The innermost layers coordinate with the functioning of the rest of the body. When I see a

The innermost layers coordinate with the functioning of the rest of the body. When I see a spider, cold cognition recognises the visual pattern, hot cognition gets worried, the body is informed that its heart should race in preparation for fight-or-flight action, and cold cognition prepares the instructions to jump. The layers work together as an integrated whole.

spider, cold cognition recognises the visual pattern, hot cognition gets worried, the body is informed that its heart should race in preparation for fight-or-flight action, and cold cognition prepares the instructions to jump. The layers work together as an integrated whole.

This week’s blog explores how the outer layer, the cortex, works.

The Outer Layer (aka The Cortex)

As we’ve seen, the cortex is big in humans compared to other animals. The back and the front do different things.

The cortex, is a sheet of neurons for processing information. The sheet of neurons, 2 millimetres thick, is just a bit smaller than a sheet of A3 paper, and it needs to be crumpled up to fit it in the skull. The sheet processes information without caring too much about the results. Where you are on the sheet doesn’t radically change how the information is processed, it just changes what is processed.

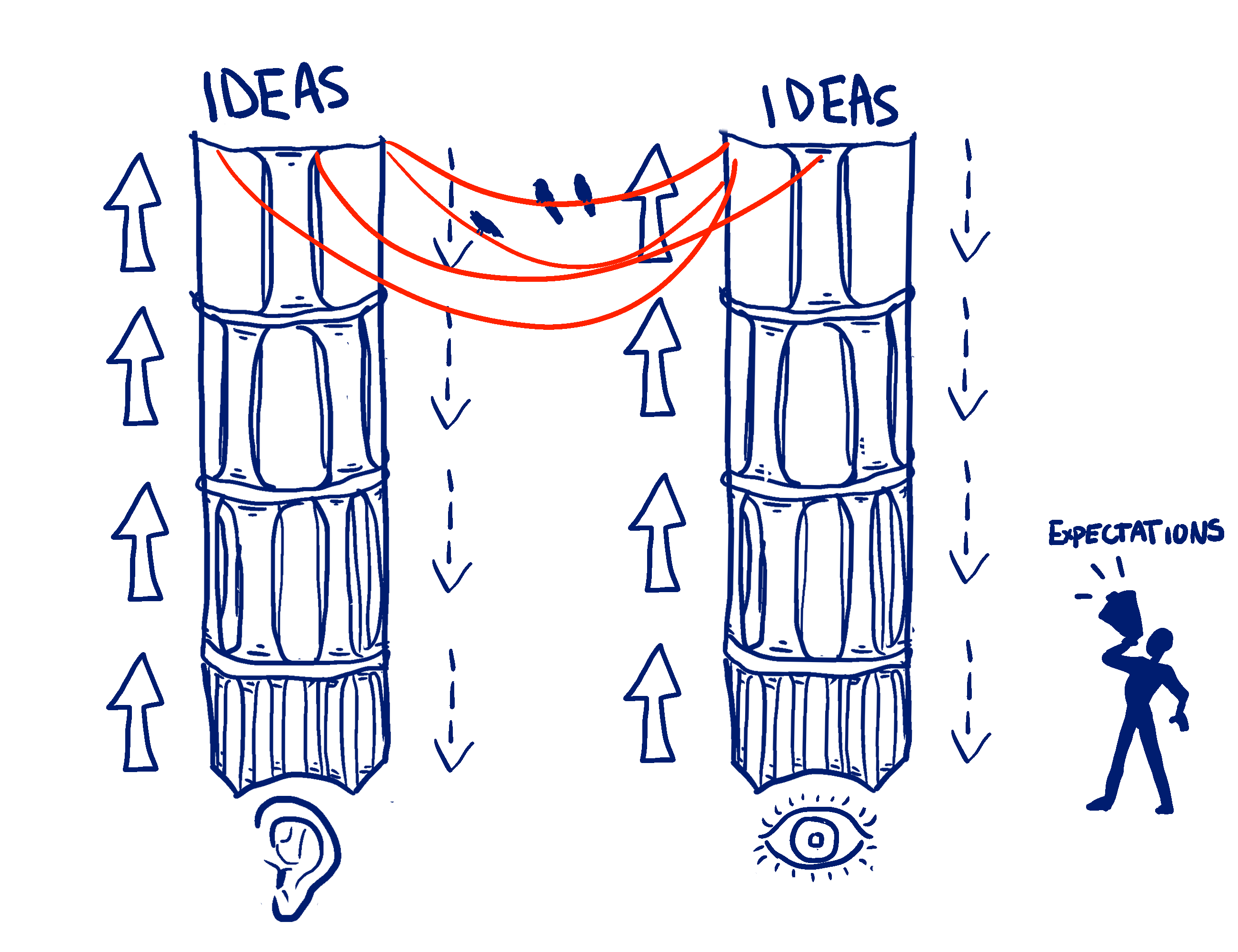

The back part of the cortex houses regions involved in sight (vision), hearing (audition), and the processing of space. Senses are processed along two routes. One route, called the ‘what’ pathway, tries to identify what things are. The other route, the ‘where’ pathway, processes where things are in space. You might want to combine this information: catch a cricket ball (howzat!) but don’t catch a snowball (duck!).

The motor areas are towards the front. At the boundary is an area for sensing the body, and the motor circuits for controlling parts of the body. Further towards the front are areas involved in planning, decision-making, and control. As we’ll see, these are still sort of motor circuits.

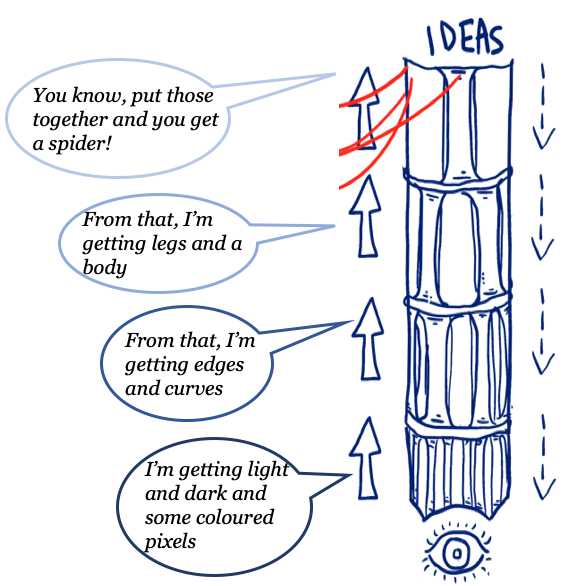

Between the back and the front, the sensory and motor systems are organised in hierarchies, moving from simple to complex. You can think of these hierarchies as being like a tower with many floors, with a separate tower for each sense. Each floor combines the work done below, and each floor has a farther view than the floor below. The lowest floor spots patterns in sensory information. The next floor up spots patterns within patterns. The next floor, patterns within patterns within patterns. Sensory and motor systems are trying to see patterns within patterns within patterns – and then make connections between the  patterns.

patterns.

After a while, the upper floors of the towers might know a thing or two about what patterns are likely. Based on their knowledge, the upper floors like to make suggestions to the lower floors on what they may be perceiving (just to help out, mind). The upper floors of the towers for the different senses talk to each other, across cables strung between the upper floors, to see if they can agree what’s out there in the world. The upper layers are connected to the frontal parts of the brain, to pass on conclusions and see if their view fits with expectations.

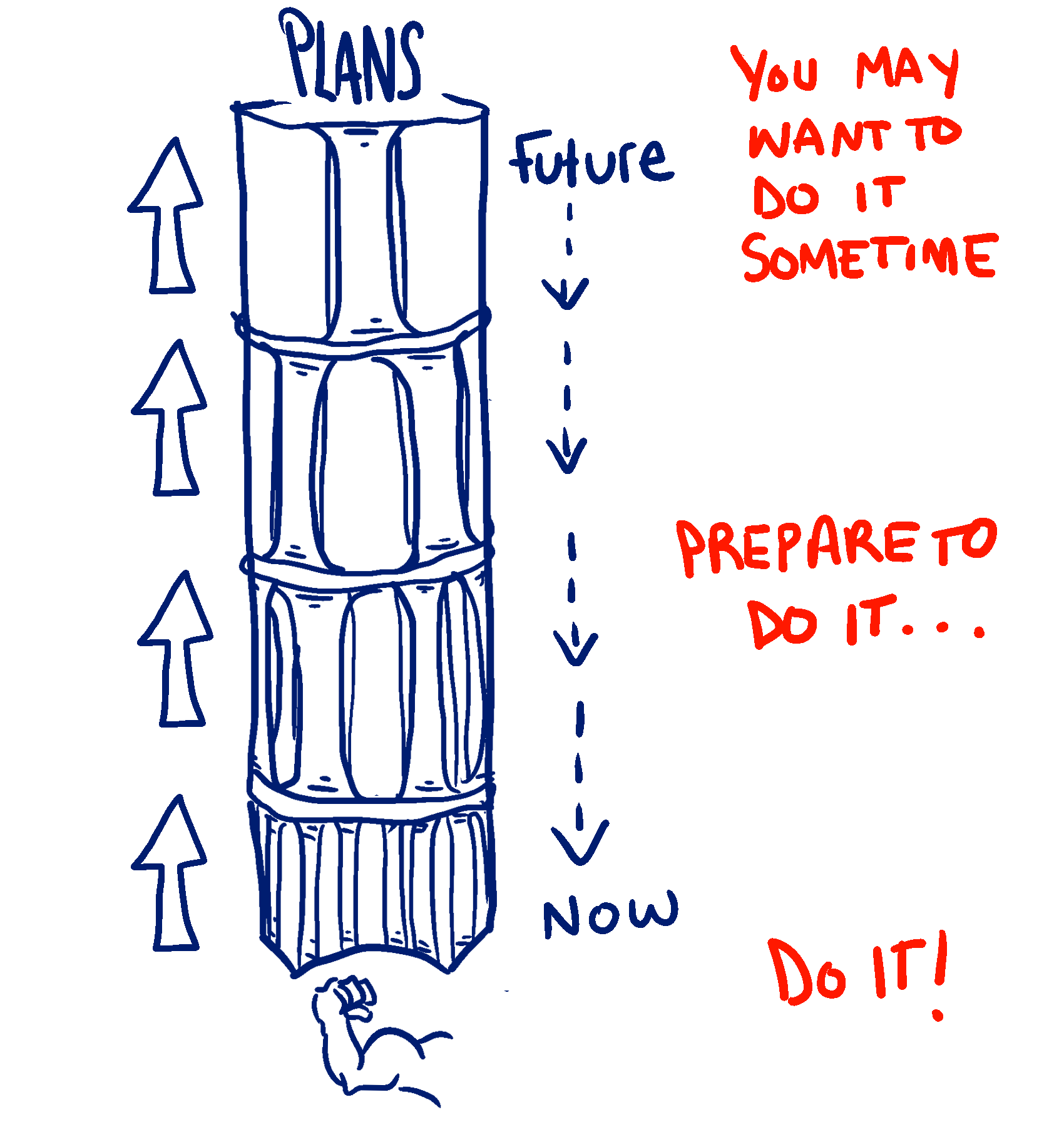

The motor system has a hierarchy too, but its higher levels are different. They’re about patterns more distant in time. The lowest levels are about immediate actions. The higher levels are about more complex sequences of actions, further forward in time. The lowest level says ‘Do it!’ (primary motor cortex). The next layer says, ‘Prepare to do it’ (supplementary cortex). The next layer up says, ‘You may want to do it sometime in the future’ (prefrontal cortex). A complex sequence of motor actions to be carried out at some future point in time can be described as a plan. Pre-frontal cortex, the planning and decision-making part of the brain, can also be seen as the top of the motor system hierarchy, looking the furthest forward in time.

We saw in the section on evolution that humans have more cortex. This means that humans can build their towers higher than other animals. In their senses, humans can discern more patterns within patterns, more complicated concepts; and in their motor systems, they can build further forward, creating plans into the more distant future.

Read more at howthebrainworks.science!