We are delighted to introduce Shafina Iqbal Vohra, who has very kindly shared her thoughts with us about research in education.

Shafina is very busy! She is an A-Level psychology teacher and part-time PhD student. She is also:

Shafina is very busy! She is an A-Level psychology teacher and part-time PhD student. She is also:

- a Certified LEGO Education® Academy Teacher Trainer

- a LEGO Innovation Studio Lead

- Head of faculty – academic options

- a Continuous Professional Learning lead.

Shafina, thank you for taking the time to answer our questions. Firstly, how do you keep up-to-date with the latest education research?

Reading. I follow various researchers, journals, articles, magazines, speakers, setups, education providers, government, and NGO bodies (WEF, UN, OECD, LEGO Foundation). I also attend seminars and conferences where possible (given the limitations of a teaching timetable) and network by meeting key individuals in education research. Recently, I have also been invited to various public events whether it is volunteering at charitable education-led events (usually related to STEM i.e. Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths), or whether I am a speaker on a panel for education and creativity. These have included the Bett Show, EdTech Podcast (coming up), TEDxTalk (The hand that rocks the mind: Learning through hands-on processes), or events such as Mayor of London RECODE, Mayor of Newham festival, and Institute of Imagination with the London Brain Project which I really enjoy! Whenever there is opportunity to learn more about the kinds of research that is being undertaken or possibilities for future research, I try to make it!

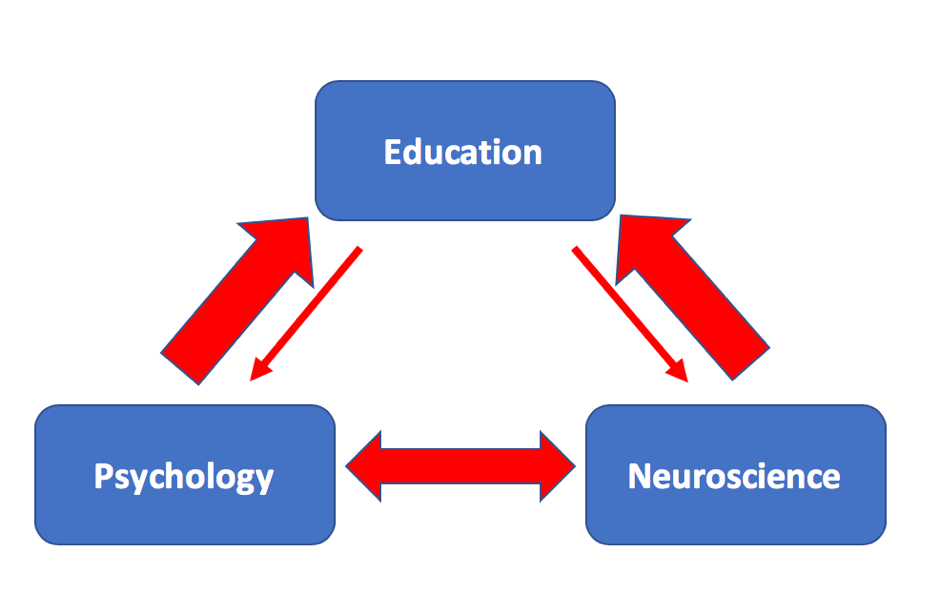

Is it important to you whether the research uses particular methods (e.g. neuroscience, classroom-based)?

I am equally interested in pure neuroscience/lab-based methodology and classroom/field-based methodology. I strongly see the benefit that the two bring together as they are an excellent way of unwrapping the relationships between the neural correlates of particular functions and the consequential or preceding behaviours we see in classrooms. Of course, there is always the debate about whether it is too simplistic to relate learning to regions of the brain directly, as functionality is all connected to a large degree. But to understand for example specific behaviours or specific challenges, neuroscience is of huge value as it equips us with direct evidence, and then allows educators to apply such understanding to their classrooms. This has huge positive impact. Similarly, classroom-based methodology provides researchers with the direct observable behaviours that also offer huge insights into learning such as how giving tools (in my case, LEGO) can enhance learning, creativity, problem solving and collaboration for the learner which may not always be simple to assess neuroscientifically.

Could you tell us how research has influenced your teaching?

As I teach Psychology and am a researcher myself, I have applied research directly to my teaching and vice versa. Understanding the teenage brain and circadian rhythms for example, has led to my rearranging what when & how I teach, which has resulted in positive learning experiences for my students. Knowing that the Basic Rest Activity cycle exists throughout the day at 90 minute intervals enables my teaching to be planned accordingly. For example, in a lesson after lunch students may feel sleepy, so I ensure that heavy thinking and listening does not continue for too long, knowing that they may lose attention. I have therefore developed hands-on methods that are engaging, less strenuous, and yet still productive.

Research has also shed light on understanding multi-sensory input and how this leads to much more activity in the brain across various regions. This has also informed my teaching practice as I ensure my lessons are a good mix of visual, tactile & auditory stimuli to enhance learning. This improves consolidation as the learners experience the learning through various forms hence repeating the content, leading to better memory and retrieval as they can attach a context to it too.

What do you think researchers should focus on next (i.e. what are the gaps in our understanding, from a teacher’s perspective)?

Research from the LEGO Foundation (here and here) has recently verified that play-based learning (early years) is key to motivated learning, independence & resilience – these are key factors that leaners need throughout education. More research in this area (as I am doing) is needed for secondary education. The amount of research on the teenage brain is increasing, but understanding how to engage demotivated teenagers who are experts in some things (gaming, social media, tv) but still maturing in others (prioritising work, taking responsibility for not doing things or accepting constructive criticism) is needed for improving teaching rather than teaching purely for assessments. I feel that research into hands-on learning and innovative thinking in the classroom is needed more than ever to improve the quality and quantity of skills-ready individuals.

Do you have any suggestions of how communication and collaboration could be improved between teachers and education researchers?

It should be easier for researchers to work in schools as this is where 6-7 hours of a child’s learning in the day takes place. I also feel that teachers should be heavily involved in research as they are at the forefront of understanding what works and what does not on a daily basis, whilst some researchers may not have extensive classroom experience. An improved dialogue between teachers and researchers would lead to stronger evidence-based research in real settings (classrooms) where natural behaviours are permitted. The collective effort of both teachers and researchers would allow for more fluidity in research, addressing issues at both the behavioural and neuroscience level together that could then have an impact on policy and curriculum. For example, my research question is based on what I have directly experienced in my teaching; a sizeable, observable impact on learners’ motivation and progress when using LEGO. This has led me to examine evidence for hands-on learning which could then be embedded across many subjects to enhance progress and learning.

Please could you describe a research-informed idea that you feel has had a positive impact in your classroom, so that others could try it as well if they feel it’s relevant. (e.g. Why did you introduce the idea? What did you do? What impact has it had?)

My approach in teaching & learning is to bring real life to the classroom. There are many ways of doing this effectively, using tried & tested activities. However, for me as an adult if someone says “let’s play…” I am instantly excited. It is human nature to play and have fun and the positive implications this has on the brain has been demonstrated through much research in early years (PEDAL, Cambridge).

Through my own experience of teaching science to KS3, I have found that children love to play even at secondary level. They want to enjoy school, they want to make things, and they want to use something in the learning that grabs them, that excites them. There is a lot of content to cover in our new curriculum. So, for me to enjoy teaching and my learners to enjoy learning, I introduced some very simple methods of learning and revising using LEGO (as per research on play), alongside more typical activities such as film, documentary, field experiments, plus the usual essays and tests they have to do.

I adapted the LEGO Foundation 6-bricks concept, for A-level Psychology using a regular 2×4 LEGO System brick. I use it in various ways whether it is to teach localisation of function (Broca’s Area, Motor Cortex, Somatosensory Cortex, Frontal Lobe, etc.) by colour coding LEGO bricks to coloured regions on the brain (from the web). An idea from the London Brain Project (Beading the brain) inspired me to create lessons using LEGO for tasks that allow students to engage with the difficult names of regions and also to use their hands, learn, laugh and remember. Added to this, I developed the 6 brick concept for research methods where students have to use 6 bricks to create things about research methods and these are usually fantastically creative, very innovative and simple and clear – it engages them with the concepts that are sometimes difficult to grasp or imagine. I also use LEGO Education’s research work on play and STEM learning by using their “Build To Express” kits to allow students to create key studies in Psychology using the LEGO which acts as a self–differentiated activity. For me it is about my learners valuing their learning and actively thinking.

The impact to my lessons has been tremendous as it means learners have different tools at hand to choose from, they become independent, they collaborate and facilitate within their own groups and it gives them a tangible memory trigger to aid their revision and exam success.

Thank you Shafina!

At CEN, we are keen to hear views from all the stake-holders of an evidence-based approach to education. In this blog, we are delighted to welcome David Weston, founder and CEO of the Teacher Development Trust. David is also Chair of the Department for Education’s Teacher Development Expert Group. He is an author, school governor, a former secondary maths and physics teacher and a Founding Fellow of the Chartered College of Teaching.

At CEN, we are keen to hear views from all the stake-holders of an evidence-based approach to education. In this blog, we are delighted to welcome David Weston, founder and CEO of the Teacher Development Trust. David is also Chair of the Department for Education’s Teacher Development Expert Group. He is an author, school governor, a former secondary maths and physics teacher and a Founding Fellow of the Chartered College of Teaching.