The Learning and Reasoning Group brings together researchers from multiple disciplinary perspectives with the aim of elucidating the mechanisms of learning and reasoning and considering pathways to informing education and artificial intelligence.

The group hosts public seminars with experts in cognition, development, artificial intelligence, and education. If you would like to be notified of future Learning and Reasoning Group events, please complete this form.

The Learning and Reasoning Group is organised by Dr Selma Dündar-Coecke. Previous organisers include Semir Tatlidil and Matthew Slocombe. For enquiries, please contact learningandreasoning@gmail.com

Forthcoming Seminars

Compositional Approaches in Cognition

Dr Sean Tull, Quantinuum

Wednesday 15 March, 4:00 pm – 5:30 pm London, UK

Online. Register here.

Previous Seminars

Causal Reasoning: Its role in the architecture and development of the mind

Prof Andreas Demetriou, University of Nicosia

Abstract: The seminar will first outline the architecture of the human mind, specifying general and domain-specific mental processes. The place of causal reasoning and its relations with the other processes will be specified. Experimental, psychometric, developmental, and brain-based evidence will be summarized. The main message of the talk is that causal thought involves domain-specific core processes rooted in perception and served by special brain networks which capture interactions between objects. With development, causal reasoning is increasingly associated with a general abstraction system which generates general principles underlying inductive, analogical, and deductive reasoning and also heuristics for specifying causal relations. These associations are discussed in some detail. Possible implications for artificial intelligence and educational implications are also discussed.

The Limits of Causal Reasoning in Human and Machine Learning

Prof Steven Sloman, Brown University

Abstract: A key purpose of causal reasoning by individuals and by collectives is to enhance action, to give humans yet more control over their environment. As a result, causal reasoning serves as the infrastructure of both thought and discourse. Humans represent causal systems accurately in some ways, but also show some systematic biases (we tend to neglect causal pathways other than the one we are thinking about). Even when accurate, people’s understanding of causal systems tends to be superficial; we depend on our communities for most of our causal knowledge and reasoning. Nevertheless, we are better causal reasoners than machines. Modern machine learners do not come close to matching human abilities.

Learning and reasoning at different levels of Pearl’s Causal Hierarchy

Dr Ciarán Gilligan-Lee, University College London

Abstract: Causal reasoning is vital for effective reasoning in many domains, from healthcare to economics. In medical diagnosis, for example, a doctor aims to explain a patient’s symptoms by determining the diseases causing them. This is because causal relations, unlike correlations, allow one to reason about the consequences of possible treatments and to answer counterfactual queries. In this talk I will present two recent causal inference projects done with my collaborators. One of which is concerned about the ability to disentangle the effect of multiple treatments in the presence of hidden confounders. The other is about how one can learn and reason with counterfactual distributions. In both cases I will strive to motivate and contextualise the results with real word examples. Along the way I’ll discuss the distinction between learning and inference in the context of a causal model. The talk is based on the following two papers: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2109.01904.pdf and http://adrem.uantwerpen.be/bibrem/pubs/JeunenWHY21.pdf.

Fast and slow learning in humans; the case for multiple parallel learning systems

Prof Denis Mareschal, Birkbeck, University of London

Abstract: It is commonly claimed in the world of AI that humans are unique in their ability to learn from a single for a small set of learning examples. In the current talk, I will review the evidence that infants, children and adults are able to learn and generalize from a single example. We will also show that other species can also learn from single examples under appropriate circumstances, and that in many domains, infants, children, and adults need many many examples to learn effectively. I will argue that this provides evidence for multiple learning systems working in parallel at all times. One illustration of this interaction will be presented in the context of interactions of cortical and hippocampal learning systems. Finally, putative implications for education will be discussed.

Argumentation in science and religion: what does educational research have to say?

Prof Sibel Erduran, University of Oxford

Abstract: Many issues facing everyday citizens require understanding of how knowledge works in different disciplines. For example, the Covid-19 pandemic has created a context that demands understanding not only of science but also of ethics, economics and politics, for example. It is increasingly becoming more important to foster cross-subject teaching and learning in schools in order to ensure that future citizens can effectively engage in meaning making around key issues facing them in their lives. One cross-curricular scenario involves science and religious education. Both subjects address big questions such as “what is the origin of the universe and life?” and as such, both subjects lend themselves for cross-curricular consideration. Argumentation, or the justification of knowledge claims with evidence and reasons, is one example that applies to the curricula and syllabi of both science and religious education in England. The purpose of this presentation is to share some research from the OARS Project funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation which focused on argumentation in the context of science and religious education (RE). The 3-year project engaged science and RE teachers in a continuous professional development programme about argumentation. Data from the teachers as well as their Key Stage 3 students have been collected to investigate through qualitative and quantitative methods how argumentation can help cross-curricular collaboration in schools. Findings will be shared which will include how teachers and students interpret argumentation in both science and RE contexts.

Compositional reasoning with process theories

Dr Aleks Kissinger, University of Oxford

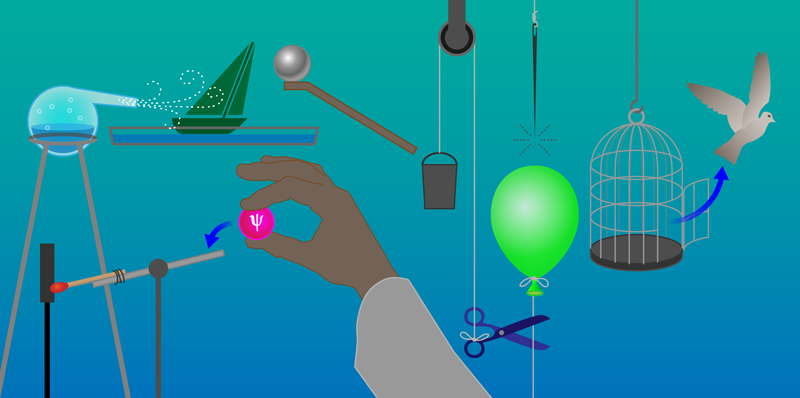

Abstract: I’ll explain process theories, which give us a very general way to reason compositionally about physics, language, logic, and pretty much anything else that happens in our heads or in the world. The key tool used in the process theory approach are diagrams, which describe how basic processes are plugged together to form more complicated ones. In this talk, I’ll give a demonstration of process theories, and their ability to explain complicated ideas without sophisticated mathematics. First, I’ll show how to put a process theory together from a bit of high school mathematics and use it to explain how cryptography works. Then, by a little “twist” (namely: changing the process theory when you’re not looking), I’ll show that the same trick used in cryptography can also be applied to do something much more surprising: quantum teleportation. Finally, I’ll conclude with a bit of a teaser of an experiment in the works to teach high-schoolers quantum theory using these ideas.

The hands of time: Dissociations between temporal language and temporal thinking

Prof Daniel Casasanto, Cornell University

Abstract: Do people think about time the same way they talk about it? Not always: apparently, not even the majority of the time. In this talk, I will explore some systematic dissociations between temporal language and temporal thinking in speakers of English, Dutch, and Darija, a Moroccan dialect of Modern Arabic. Analyses of spoken space-time metaphors reveal a fundamental fact of humans’ temporal thinking: It depends on spatial thinking. Yet, essential features of the space-time mappings in our minds may be absent from language. Our interactions with both the physical environment and social environment can determine the implicit ‘mental metaphors’ we use to structure our temporal thinking, giving rise to incongruities between temporal language and thought that remained hidden throughout decades of research on space-time metaphors.