Jane, you’re a leading practitioner in the treatment of dyslexia and dyscalculia, and through your books “The Dyscalculia Assessment” and “The Dyscalculia Solution: Teaching number sense”. You’re a Freelance SEN advisor to Independent School Groups. You’re also involved in Learnus, a think tank that supports the translation of educational neuroscience research into the classroom. What keeps you busy at the moment?

Jane, you’re a leading practitioner in the treatment of dyslexia and dyscalculia, and through your books “The Dyscalculia Assessment” and “The Dyscalculia Solution: Teaching number sense”. You’re a Freelance SEN advisor to Independent School Groups. You’re also involved in Learnus, a think tank that supports the translation of educational neuroscience research into the classroom. What keeps you busy at the moment?

Currently, I’m informally assessing undiagnosed primary pupils, investigating evidence for diagnoses of dyslexia, dyscalculia and other related conditions such as dyspraxia and attention deficit disorder. For the undiagnosed pupils, my goal is to triage what are the best interventions given the spikes in their profiles and attainments, sometimes involving reports from educational psychologists, when parents need advice on where to go from these, and what interventions to select.

At the CEN, we’re really interested in how the characteristics of individual children link to the best interventions to alleviate their difficulties. Based on your extensive experience, can I ask how you’ve addressed that challenge in your own practice?

Well, I taught many dyslexic pupils to read and spell and dyscalculics to achieve basic mathematical skills over the years, with many successes. I adapted my approach from an extensive toolbox to refine my approaches, depending on what I observed in the pupils. I was fortunate enough to teach most individually, so few compromises were necessary as would be needed teaching even two pupils or small groups. Classroom interventions tend to encompass a more scattergun approach, which might lead to some positive results but would be achieved more slowly.

I think a good starting point is always an analysis of what type of difficulty a dyslexic or dyscalculic pupil presents. In the past, I saw many pupils who could not read, or spell and so had the chance to really start from the beginning with the non-reader. Here’s a link to a resource describing different types of dyslexia put together from the blogs delivered regularly from www.readandspell.com, a touch-typing programme long used at Emerson House.

Identifying dyslexia types is intended to make treatment easier. Six are often distinguished: (1) phonological (problems breaking words into sounds), (2) surface (problems processing language when children move beyond the decoding stage, (3) visual (trouble reading and remembering what has been seen on the page), (4) primary (runs in families, more often in males and left-handers), (5) secondary / developmental (due to problems in early development, responds best to treatment such as targeted phonics work through computer programs), (6) trauma / acquired dyslexia (due to disease or brain damage).

The touch-typing (i.e. typing on a keyboard) programme used currently at Emerson House provides an opportunity to overlearn the spelling of common vocabulary and other words that reinforce sound-letter correspondence, and for dyslexic children to build achieve confidence in an academic environment, which may have been dented by their struggles in learning to read. It takes a multi-sensory approach, combining spoken words, visual words, and breaking each into their components during the touch-typing task.

Most dyslexics respond well to technology that breaks learning down into bite-size units. It allows them to proceed through a course at their own pace, learning one step at a time and repeating modules until they are ready to move on.

This type of overlearning is very helpful and can also benefit children with attention deficit disorder/ attention hyperactive disorder and other specific learning difficulties.

Cuisenaire Rods

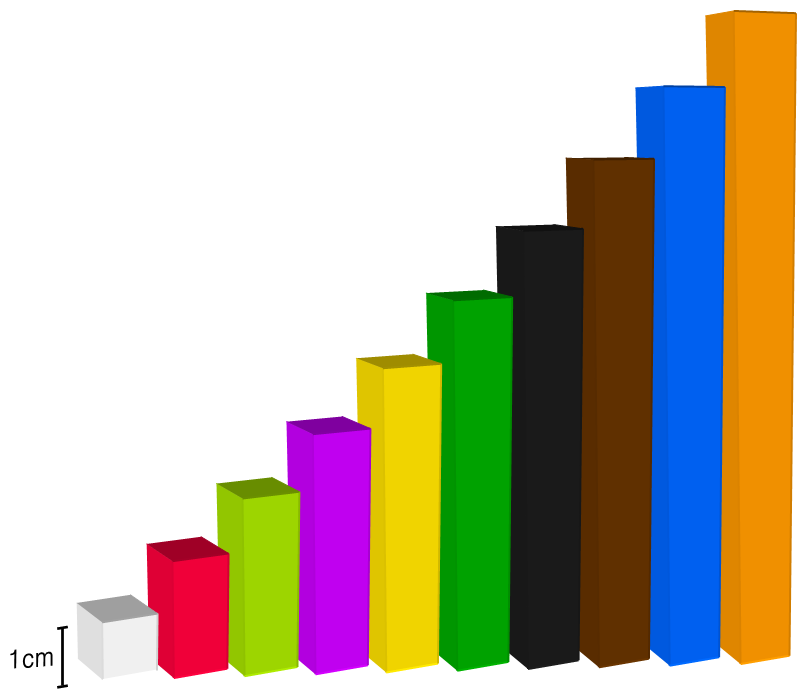

In the case of dyscalculia, it is essential to combine multi-sensory teaching of numerical quantitative approaches with the use of concrete materials such as counters, a Slavonic Abacus, Cuisenaire Rods, Base Ten Number Concept material to reinforce place value understanding, as well as other more advanced visual learning approaches. A useful reference here is the book of Tandi Clausen May, Teaching Mathematics Visually and Actively, for pupils 7 to 16 years.

Is the use of multi-sensory approaches best in disorders? Isn’t there a risk of confusion, of information overload?

I believe that the brain works as one entity with specialist areas responding more to different types of stimulations, and surely a brain that is wired differently in a dyslexic or dyscalculic learner, might then select and respond to which particular modalities makes sense. If you deprive a pupil from some auditory, visual or tactile inputs, then you might be removing the very modality that they can use to process information. Do you teach to strengths or weaknesses?

Some programmes target only weaknesses and leave the pupils struggling. Surely it’s better to follow strengths to develop compensatory strategies, but not to ignore weaknesses either. A combined approach is necessary.

In The Dyslexia Project at Stanford, Professor Bruce McCandliss found that Sound/Letter reading increases neural input activity in areas best adapted for reading. Apart from my own positive experience with it, the touch-typing approach may be worth evaluating more systematically to explore its effectiveness. It addresses phonics from the very beginning in terms of pure letter by letter correspondence which then develops into orthographic patterns (such as silent ‘e’ or split vowels) quite quickly. I have seen pupils with virtually no literacy, learn to read and spell almost on this programme alone, although they did also combine this with carefully selected reading books.

Are there any further programmes for dyslexia that you recommend?

I have recently trained for 4 days on one of the most up to date programmes, with the latest edition from 2018, called Sounds-Write. It is a highly structured programme that teaches pupils to precisely analyse the sounds in each word and then moves from the sounds to the written word. It is a reversible programme in that the route develops initially from the sounds to the letters for spelling, and then from the letters back to the sounds for reading.

Another current programme that I have found useful is Phonics Hero. I tried the beginning of this on my grandson age 4 years old, and I thought it was a well-designed and enjoyable programme. It is a phonic programme but adds in sight/red words such as ‘the/was’, right from the start, which I like. I count ‘and’ as a phonic word, but ‘the’ is particularly difficult because of the possible f/th confusion, as well as the voiced feature in ‘the’ versus voiceless in ‘thin’.

What is it you check for in pupils to guide what work you do with them?

Going back to types of dyslexia, in my current work I tend to check if pupils can spell basic regular words that are phonically transparent, with success. This would include regular three letter words such as ‘cat’, up to complex triple blends such as ‘strap‘. I also see how they are getting on with alphabet names of the vowels as in ‘he/no’ and if successful, go on to look at ‘day/my‘. This is because many schools don’t teach the names of the vowels very early on, even though they are needed for basic word such as ‘day’, ‘he’, ‘my’, and ‘no’. Looking at these gives clues as to auditory analysis versus the first evidence of spelling with visual memory for ‘my’ rather than ‘mi’ for example. The words ‘moon’ and ‘look’ are always good ones to check as they are hard in terms of ‘oo’ and ‘k/ck’ choices as well as developing memory for digraphs ‘sh’ and ‘ch’ which are often confused.

Currently, in terms of diagnosis, I have been looking at spelling for the so-called classic dyslexics who have marked phonological difficulties, so can’t even spell basic words phonetically. This is in contrast to those who can’t visually recall basic words where there are orthographic choices to be make even with ‘sh/ch/th’, for example, as well as ‘k/ck’ choices as on ‘look‘ and ‘back‘. I have been calling these visual dyslexics who I see as having poor visual recall.

In my view, spelling is the avenue for quickly analysing where the pupil has got to and if they can be seen as phonological dyslexics or visual dyslexics.

So you view spelling as telling you more about the child than reading?

Yes I do. Of course, one can also analyse their reading and see if they have developed only phonetic reading or have also developed visual recognition skills for common and irregular words.

Reading conceals exactly how pupils are decoding as they may be able to read using strong oral language skills as well, or guess from the pictures. One can see exactly what a pupil has grasped from spelling, along with analysing errors precisely to notice if they are spelling phonetically, or by visual recall or a combination.

I quite like the Ruth Miskin approach of calling regular words ‘green words’ and irregular words ‘red words’, as it seems to be a clear and simple guide for the pupils to predict what type of word it is.

I have seen many pupils who arrive at 6 or 7 who are applying only phonic decoding approaches and clearly have virtually no ‘sight’ vocabulary – that is, red words are difficult for them. I used to call these pupils ‘phonically constipated’  These children need taking back to the beginning, to develop fluency from the start. So I do believe in including some basic red words from the start to achieve fluency more quickly.

These children need taking back to the beginning, to develop fluency from the start. So I do believe in including some basic red words from the start to achieve fluency more quickly.

The Sound-Write system supports the foundations of reading as a sound based system they call The Initial Code which is transparent, and moving on to the Extended Code involving the orthographic stages for decoding and encoding words that are not immediately transparent, such as ‘rain’ and ‘night’ for example.

I was never keen on ‘Tom ran up the hill to the red van’, which can be taught without much context whatsoever. Instead I always used some sort of story, to make things meaningful for the child from the start. This doesn’t necessarily mean using ‘predictable’ text but including decodable text from the start, with some meaning added in, such as pictures and characters names that carry through, rather than changing with the next book. This has led me to question what I mean by phonological dyslexics and visual dyslexics, as different specialists use different terms. In the past I thought that Uta Frith made the distinction clear with her work on the alphabetic (phonic) stage, followed by the orthographic stage.

Could you give us some more specific guidance in terms of how spelling errors map to dyslexia type?

One good source was the introduction to Sacre and Masterton’s The Single Word Spelling Test. It might be possible to buy it second hand now. I used this test quite a lot and am keen on it as it’s straightforward and yet gives complex analysis. Not only does it analyse spelling errors but also provides a teaching plan based on the errors found. In addition it is standardised so you might find it very useful as a basis of looking at spelling for research purposes. The authors looked at phonological errors versus visual errors. They see phonological errors in three categories: non-phonetic errors: ‘hit’ for ‘hot‘, phonetically simple errors: ‘mac‘ for ‘make‘, and phonetically complex errors: ‘maik‘ for ‘make‘.

As a matter of fact, I don’t categorise homophone errors ‘make/maik‘ as phonetic errors, but instead visual/orthographic errors that involve visual recall skills in the visual dyslexic, who can’t proof read after they have written the word either. In my opinion, ‘make/maik’ are both phonetically accurate/plausible rather than wrong, as far as making visual recall choices. There’s a debate in the making.

Sacre and Masterton go on to classify visual errors as ‘ambiguous’, because it’s hard to know if it’s a phonological error or a visual error. I believe that plausible spellings such as ‘stashun’ for station are visual errors because the auditory processing has worked perfectly, but the visual recall has not. The pupils I see often have good visual recognition for reading, so read quite well, but very poor visual recall for spelling.

The Sound-Write programme would classify by error analysis which would indicate the needed revision of the Extended Code for the different ways of spelling ‘shun’ for example in station, mansion etc.

Do you remember how you learned to read?

Well, I am not dyslexic and do remember learning to read, perfectly visually. The words ‘Peter and Jane’ were seen as ‘pictures’ of a word rather than sounds. I also spelt very well, as I could recall the appearance of the words very easily. I may have had some early alphabetic teaching but I can’t remember that at all. I certainly only became explicitly aware of phonics, and word patterns, when training on The Hornsby Course for specialist teaching of dyslexics.

What would your diagnostic tips be for reading, rather than spelling?

As far as looking at reading, I don’t usually use a test in order to analyse visual errors versus phonetic errors. I judge visual errors as confusing visually similar words and phonetic errors as making errors with the letter to sound correspondences, so that a nonsense word might be produced if the phonetic decoding of unknown words is poor.

Where can we find out more about current debates in reading research and teaching methods?

In order to see what is currently debated, I can recommend Mark Seidenberg’s Language at the Speed of Sight from 2017 and Lyn Stone’s work from Australia, Reading for Life, from 2019. I am following the Australian debate via Spelfabet (where the topic is heated at present, with arguments about decodable versus predictable texts). Reading was thought by many in the past as a Psycholinguistic Guessing Game. The term ‘balanced’ teaching seems to be a no-go area now and the debate can still be polarised. I think the baby might be thrown out with the bath water, as it is perfectly possible to use many tools from a tool box without ignoring certain ones.

If you fit your teaching to the pupil in front of you, as an experienced teacher can, then that is the way to go, in my opinion. If binary arguments persist, then the fiery debates will continue without compensatory routes being considered.

Plan help based on the pupil, rather than pick a programme for everyone. However, the Sound-Write programme would be ideal for the less experienced as it has clear teaching protocols. Once the newly qualified become familiar with it, then judgements can be made, based on experience and designed to fit pupil profiles more precisely, depending on error analysis and the stage they are at in literacy.

Thank you so much for your time!

Jane was being interviewed by Michael Thomas, Director of the Centre for Educational Neuroscience.

Useful Books:

- Reading in the Brain by Stanilas Dehaene.

- Proust and the Squid by Maryanne Wolf

- Reader Come Home by Maryanne Wolf

- English Spellings, A Lexicon by David Philpot et al. (Sounds-Write based)

Hi Keri,

Hi Keri,

These children need taking back to the beginning, to develop fluency from the start. So I do believe in including some basic red words from the start to achieve fluency more quickly.

These children need taking back to the beginning, to develop fluency from the start. So I do believe in including some basic red words from the start to achieve fluency more quickly.