Environmental and genetic causes of individual differences in educational achievement

Blog written by Professor Michael Thomas

The nature-nurture issue is well-known amongst teachers: children differ, and some of these differences are due to the children’s nature, some due to the environment they are raised in, and some a combination of children’s different natural reactions to the environments they are raised in.

Gaps in educational achievement between children are a key issue for society, and their causes have been a focus for research in the social sciences. These gaps have spurred educational neuroscience investigations into possible underlying brain mechanisms, with separate work in the areas of environmental influences and genetic mechanisms.

Nurture

With respect to environmental influences, research has focused on the effects of socioeconomic status (SES), one of the environmental measures showing most predictive power on cognitive and educational outcomes. SES is usually measured by parental levels of education and income. Notably, SES differences in cognitive abilities are already observable when children start school, and tend not to narrow with age (e.g., Hackman et al., 2015), and may even widen. For example, von Stumm and Plomin (2015) reported that in a large sample of almost 15,000 UK children followed from infancy through adolescence, children from low SES families scored on average 6 IQ points lower at age 2 than children from high SES backgrounds but by age 16, this difference had almost tripled. Notably, the differences in cognitive ability in school-age children associated with SES tend to be larger than the effects produced by different schooling (e.g., Walker, Petrill & Plomin, 2005). The greater effects of the home than the school on cognitive ability suggest that educational neuroscience must retain a focus on developmental factors beyond the classroom.

SES as a measure of the environment is only a proxy for the actual experiences of the child and therefore the actual causal mechanisms. These mechanisms may operate along multiple pathways, and those pathways may differ depending both on the absolute level of poverty across countries and the level of inequality. These pathways include prenatal factors, such as maternal diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, and stress; postnatal nurturing factors, such as early caregiver sensitivity; and the richness of postnatal cognitive stimulation (Hackman, Farah & Meaney, 2010; Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2016). Notably, the effects of SES are uneven across cognitive profiles, with relatively greater effects on language development and executive functions, and weaker on visuo-spatial cognition (Farah et al., 2006), although the reasons for this unevenness are unknown.

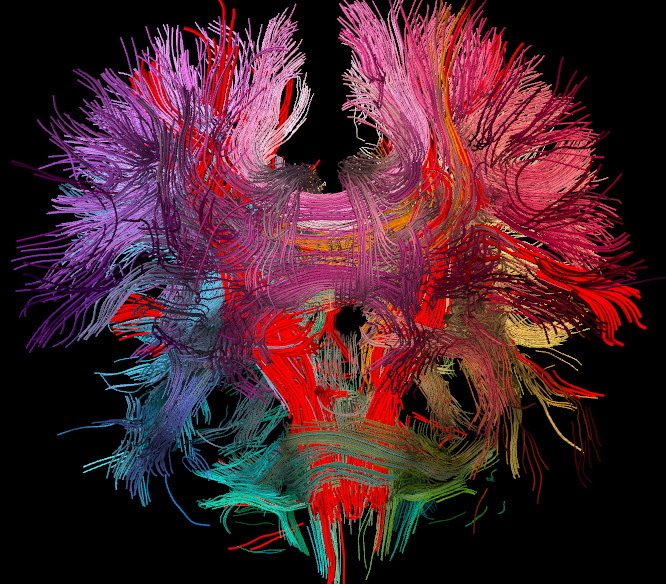

In a large US sample, Noble et al. (2015) demonstrated differences in structural brain measures of cortical thickness and cortical area correlated with SES measures, in regions that fitted with the cognitive abilities showing largest effects (temporal regions for language, prefrontal regions for executive functions). Investigations of causal mechanisms are compromised by the fact that so many correlated environmental factors are associated with differences in SES (Hackman et al., 2015); but in theory, an understanding of mechanism would suggest most effective points to intervene to alleviate the effects of poverty and deprivation on educational outcomes (Thomas, 2017).

Nature

With respect to genetics, work in behaviour genetics has begun to impact on education. Most obviously, evidence points to the heritability of differences in educational achievement. Heritability is defined as the amount of variation in behaviour explained by genetic similarity. Heritability is either inferred on the basis that achievement is more similar the more genetically similar individuals are (e.g., the idea that ability runs in families); or it is measured directly by correlating variation in individual letters of DNA (single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) to educational outcomes in large samples (though the variation in behaviour explained by direct measures of DNA variation is typically much smaller, perhaps only ~10% instead of the ~50% explained by observing patterns that run in families; e.g., Okbay et al., 2016). For example, within the last five years, papers have been published showing that the heritability of educational achievement aged 16 is up to 60%, and that controlling for IQ, it appears to be the same genes that explain variability in different academic disciplines (Krapohl et al., 2014; Rimfeld et al., 2015); that social mobility (measured as children achieving higher educational levels than their parents) is itself around 50% heritable (Ayorech et al., 2017); that, on genetic grounds, there is little evidence that selective schools produce better educational outcomes than non-selective schools (Smith-Woolley et al., 2018); and that educational achievement may be a causal protective factor against Alzheimer’s disease (Zhu et al., 2018).

There is insufficient space here to evaluate these types of claims (see Thomas et al., 2013; Ashbury & Plomin, 2014; Meaburn, in press). However, we can simply note that a genetic perspective on education emphasises that not all differences between children are environmental in origin; but as yet, does not point to specific implications for teaching. Somewhat counter-intuitively, environments that optimise learning will increase the extent to which educational success is heritable. For example, greater heritability is observed in classes with better teachers (Taylor et al., 2010), as it is in affluent families compared to impoverished ones (Turkheimer et al., 2003). This is because heritability acts as an indicator of where limiting factors lie: when better school environments reduce limits on learning, variability between children is more readily explained by their genetic make-up (Asbury, 2015; Thomas, Kovas, Meaburn & Tolmie, 2015). Increasing heritability rates could therefore be a useful indicator of reducing educational inequality.

Effects linked to genes or changes in the brain are not inevitable

The risk with both neuroscience evidence of the effects of poverty on brain development, and of genetic effects on educational achievement, is that these will be construed by educators as ‘deterministic’ or inevitable outcomes. Yet many cognitive effects of poverty can be ameliorated by intervention, such as training executive functions, because the brain is plastic (Neville et al., 2013); and previously measured genetic effects may disappear when environments are altered. Indeed, the future potential of genetics would be to predict the best, tailored environment for each child to reach his or her genetic potential. However, currently, genetic studies are focused on maximising predictive power (such as by the use of polygenic risk scores, which combine the effects of all measured DNA variation to predict differences in behaviour) – rather than informing a neuroscientific understanding of the brain mechanisms of learning that would enable such tailoring of environments.

References

Asbury, K., & Plomin, R. (2014). G is for Genes: The Impact of Genetics on Education and Achievement. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Ayorech, Z., Krapohl, E., Plomin, R., & von Stumm, S. (2017). Genetic Influence on Intergenerational Educational Attainment . Psychological Science,28(9), 1302 – 1310.

Farah, M. J., Shera, D. M., Savage, J. H., Betancourt, L., Giannetta, J. M., Brodsky, N. L., … & Hurt, H. (2006). Childhood poverty: Specific associations with neurocognitive development. Brain Research, 1110, 166 –174.

Hackman D.A., Gallop, R., Evans, G.W. & Farah, M.J. (2015). Socioeconomic status and executive function: Developmental trajectories and mediation. Developmental Science, 18(5), 686–702.

Hackman, D.A., Farah, M.J. & Meaney, M.J. (2010). Socioeconomic status and the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 651– 659.

Meaburn, E., (in press). Genetics and education. In: M. S. C. Thomas, D. Mareschal, & I. Dumontheil (Eds.), Educational Neuroscience: Development Across the Lifespan. London, UK: Routledge.

Noble, K.G., Houston, S.M., Brito, N.H. et al. (2015). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature Neuroscience, 18, 773–778.

Okbay, A., Beauchamp, J. P., Fontana, M. A., Lee, J. J., Pers, T. H., Rietveld, C. A. et al. (2016). Genome-wide association study identifies 74 loci associated with educational attainment. Nature, 533, 539–542.

Rimfeld, K., Kovas, Y., Dale, P. S., & Plomin, R. (2015). Pleiotropy across academic subjects at the end of compulsory education. Scientific Reports, 5, 11713

Smith-Woolley, E., Pingault, J-B., Selzam, S., Rimfeld, K., … Plomin, R. (2018). Differences in exam performance between pupils attending selective and non-selective schools mirror the genetic differences between them. npjScience of Learning, 3, Article number: 3 (2018).

Thomas, M. S. C. (2017). A scientific strategy for life chances. The Psychologist, 30, 22-26. http://www.bbk.ac.uk/psychology/dnl/personalpages/Thomas_Psychologist_May17.pdf

Thomas, M. S. C., Kovas, Y., Meaburn, E., & Tolmie, A. (2015). What can the study of genetics offer to educators? Mind, Brain & Education, 9(2), 72-80. http://www.bbk.ac.uk/psychology/dnl/personalpages/Thomas_etal_2015

von Stumm, S. & Plomin, R. (2015). Socioeconomic status and the growth of intelligence from infancy through adolescence. Intelligence, 48, 30–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4641149/

Walker, S. O., Petrill, S. A., & Plomin, R. A. (2005). A genetically sensitive investigation of the effects of the school environment and socioeconomic status on academic achievement in seven-year-olds. Educational Psychology, 25(1), 55-73.