In this blog, our colleague and collaborator Dr. Erika Galea, talks about how she founded and directs the Educational Neuroscience Hub Europe (Malta). Erika holds a masters in educational leadership and completed her PhD in the Department of Psychology and Human Development at University College London. Her thesis was entitled ‘Regulating Emotions in the Maltese Classroom to Improve the Quality of Teaching and Learning in the Early Years’. She has spent over two decades working in education as a teacher and in senior leadership. The Hub, founded in 2022, is focused on promoting evidence-based strategies to improve teaching and learning effectiveness, emphasising student-centred education. Erika describes the inspiration behind the Hub, and how it is achieving its goals.

Introduction and Impact

The Educational Neuroscience Hub Europe (Malta), of which I am founder and director, has been instrumental in raising awareness and transforming the mindset of educators across Malta and Gozo, from early childhood education through to tertiary education. This transformation involves council of heads, school and college principals, lecturers, senior leadership teams, curriculum coordinators and heads of departments, teachers, learning support staff, as well as psychologists, speech therapists, inclusive coordinators, social workers, and play therapists, all through its extensive training workshops.

Bridging Neuroscience and Pedagogy

By introducing the science of teaching and learning, the Hub aims to bridge the gap between neuroscience and pedagogy. As the expert leading this initiative, I am converging these two disciplines within local schools. Dialogue with experienced educators is of utmost importance, as listening to those who have been trialling and testing teaching strategies for a while is crucial for merging the neuroscientific strategies with their already effective methods. It is important to communicate to educators that this is not about completely changing their methodology, but rather about making small adjustments to enhance its effectiveness in reaching their students in the classroom.

Debunking Neuromyths

A significant focus of the training is to debunk common neuromyths—misconceptions about brain function that can hinder effective teaching practices. For instance, the belief that individuals are either left-brained or right-brained learners is a neuromyth that the Hub actively dispels. Similarly, the Hub addresses the widespread belief in learning styles and multiple intelligences, clarifying that these ideas are not supported by current neuroscientific evidence. By correcting such misunderstandings, the Hub empowers teachers with accurate knowledge, enabling them to adopt strategies that align with how the brain genuinely processes information, including the various types of memory involved.

A significant focus of the training is to debunk common neuromyths—misconceptions about brain function that can hinder effective teaching practices. For instance, the belief that individuals are either left-brained or right-brained learners is a neuromyth that the Hub actively dispels. Similarly, the Hub addresses the widespread belief in learning styles and multiple intelligences, clarifying that these ideas are not supported by current neuroscientific evidence. By correcting such misunderstandings, the Hub empowers teachers with accurate knowledge, enabling them to adopt strategies that align with how the brain genuinely processes information, including the various types of memory involved.

Evidence-Based Teaching Strategies

A key element of the training workshops is examining the influence of neuroscience on teaching strategies and embedding these approaches within the curriculum, lesson planning, and daily methodology. The Hub’s approach is grounded in evidence-based practices that adopt insights from brain research to enhance teaching methods. Teachers learn how to apply principles of neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections, which is transformative in enabling them to create more adaptable and responsive learning environments. Practical applications, discussed during the workshops, include strategies such as different modes of retrieval practice, with their lesson planning for improving memory retention, fostering critical thinking skills, and boosting overall student engagement through activities that stimulate cognitive development.

A key element of the training workshops is examining the influence of neuroscience on teaching strategies and embedding these approaches within the curriculum, lesson planning, and daily methodology. The Hub’s approach is grounded in evidence-based practices that adopt insights from brain research to enhance teaching methods. Teachers learn how to apply principles of neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections, which is transformative in enabling them to create more adaptable and responsive learning environments. Practical applications, discussed during the workshops, include strategies such as different modes of retrieval practice, with their lesson planning for improving memory retention, fostering critical thinking skills, and boosting overall student engagement through activities that stimulate cognitive development.

Integrating Emotion Regulation, Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning

Emotion regulation, metacognitive and self-regulated learning strategies are integrated into daily teaching routines, promoting both cognitive and emotional intelligence, as well as a growth mindset, among students. By incorporating these strategies into their pedagogy, teachers not only help students manage their emotions but also support their development of metacognitive and self-regulated learning skills. When students can manage their emotions, they are better equipped to monitor and adjust their cognitive strategies, leading to improved focus and more effective engagement with learning activities. Self-regulated learning further enhances this by empowering students to set goals, develop strategies, and self-assess their progress, all while managing emotional responses that might otherwise hinder their learning.

Emotion regulation, metacognitive and self-regulated learning strategies are integrated into daily teaching routines, promoting both cognitive and emotional intelligence, as well as a growth mindset, among students. By incorporating these strategies into their pedagogy, teachers not only help students manage their emotions but also support their development of metacognitive and self-regulated learning skills. When students can manage their emotions, they are better equipped to monitor and adjust their cognitive strategies, leading to improved focus and more effective engagement with learning activities. Self-regulated learning further enhances this by empowering students to set goals, develop strategies, and self-assess their progress, all while managing emotional responses that might otherwise hinder their learning.

Enhancing Retention Through Emotional Engagement, Novelty and Relevance

During the workshops, I emphasise the crucial role of presenting relevant content and introducing novelty to enhance motivation and engagement, as well as evoking emotions in teaching to improve the retention of information and skills. By adopting cognitive strategies that incorporate emotional engagement, teachers can help students not only remember content more effectively but also develop the self-awareness and self-regulation skills necessary for lifelong learning. This integrated approach ensures that students are not only managing their emotions but also applying metacognitive and self-regulation strategies to achieve more profound and sustained learning outcomes.

During the workshops, I emphasise the crucial role of presenting relevant content and introducing novelty to enhance motivation and engagement, as well as evoking emotions in teaching to improve the retention of information and skills. By adopting cognitive strategies that incorporate emotional engagement, teachers can help students not only remember content more effectively but also develop the self-awareness and self-regulation skills necessary for lifelong learning. This integrated approach ensures that students are not only managing their emotions but also applying metacognitive and self-regulation strategies to achieve more profound and sustained learning outcomes.

Workshop Structure and Impact

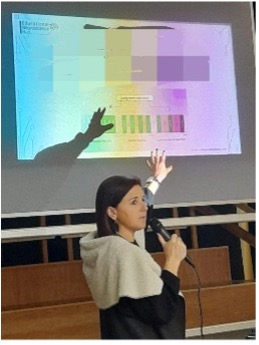

The workshops offer a highly enriching experience, divided into three distinct parts to maximise impact. The session begins with an engaging and interactive talk that presents the theoretical underpinnings of neuroscientific strategies. This is followed by collaborative, hands-on practical work designed to help educators integrate these strategies into their daily methodologies. The final component provides a platform for educators to delve deeper into these concepts, reflect on their practices, and discuss their experiences. This structured approach not only allows educators to critically examine and enhance their methods but also ensures that the strategies are practical and effective for real classroom settings.

Fostering Mindset Shifts and Engagement

Educational Neuroscience focuses on creating awareness of evidence-based approaches, necessitating a change in mindset. This shift fosters engaging and thoughtful discussions, making it a fulfilling experience and a pleasure to positively impact teaching approaches. The insightful questions posed by teachers during these workshops reflect their active engagement and critical reflection on their teaching practices. These interactions highlight the success of the various workshops in promoting a deeper understanding of how neuroscience can inform and improve educational practices. Engaging with experienced educators facilitates a rich exchange of ideas, enhancing the training’s effectiveness and providing newly qualified teachers with new strategies and teaching approaches.

Educational Neuroscience focuses on creating awareness of evidence-based approaches, necessitating a change in mindset. This shift fosters engaging and thoughtful discussions, making it a fulfilling experience and a pleasure to positively impact teaching approaches. The insightful questions posed by teachers during these workshops reflect their active engagement and critical reflection on their teaching practices. These interactions highlight the success of the various workshops in promoting a deeper understanding of how neuroscience can inform and improve educational practices. Engaging with experienced educators facilitates a rich exchange of ideas, enhancing the training’s effectiveness and providing newly qualified teachers with new strategies and teaching approaches.

National Recognition and Future Outlook

Since the training and awareness initiatives started last October, teachers and school senior leadership teams nationwide have enthusiastically embraced the educational neuroscience workshops and evidence-based practices throughout the past scholastic year, valuing the insightful and practical strategies provided. There is strong interest in expanding these workshops further, with a focus on providing adequate support during implementation and evaluation phases to measure their impact effectively. Their collective enthusiasm highlights a strong commitment to enhancing educational outcomes through the application of neuroscience principles.

The positive development is that educational neuroscience has been officially recognised and incorporated into the Malta National Education Strategy 2024–2030, which was published in March 2024. Following a consultation with the working group on the National Education Strategy at the Ministry for Education and conducting training sessions for ministry officials, I played a pivotal role in advocating for this inclusion, highlighting the recognition of the significance of educational neuroscience. This strategic move emphasises the commitment to adopting scientific insights to enhance educational outcomes nationwide. By embedding educational neuroscience into the Malta National Educational Strategy, the initiative aims to sustain and expand its impact, ultimately benefiting teachers and students across the country.

I look forward to continuing this journey in the upcoming academic year, delving further into integrating neuroscience principles into teaching and learning.

For more on the Educational Neuroscience Hub Europe (Malta), visit our website. To contact Dr. Galea, email her at: erikagalea@educationalneurosciencehub.com

A significant focus of the training is to debunk common neuromyths—misconceptions about brain function that can hinder effective teaching practices. For instance, the belief that individuals are either left-brained or right-brained learners is a neuromyth that the Hub actively dispels. Similarly, the Hub addresses the widespread belief in learning styles and multiple intelligences, clarifying that these ideas are not supported by current neuroscientific evidence. By correcting such misunderstandings, the Hub empowers teachers with accurate knowledge, enabling them to adopt strategies that align with how the brain genuinely processes information, including the various types of memory involved.

A significant focus of the training is to debunk common neuromyths—misconceptions about brain function that can hinder effective teaching practices. For instance, the belief that individuals are either left-brained or right-brained learners is a neuromyth that the Hub actively dispels. Similarly, the Hub addresses the widespread belief in learning styles and multiple intelligences, clarifying that these ideas are not supported by current neuroscientific evidence. By correcting such misunderstandings, the Hub empowers teachers with accurate knowledge, enabling them to adopt strategies that align with how the brain genuinely processes information, including the various types of memory involved. A key element of the training workshops is examining the influence of neuroscience on teaching strategies and embedding these approaches within the curriculum, lesson planning, and daily methodology. The Hub’s approach is grounded in evidence-based practices that adopt insights from brain research to enhance teaching methods. Teachers learn how to apply principles of neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections, which is transformative in enabling them to create more adaptable and responsive learning environments. Practical applications, discussed during the workshops, include strategies such as different modes of retrieval practice, with their lesson planning for improving memory retention, fostering critical thinking skills, and boosting overall student engagement through activities that stimulate cognitive development.

A key element of the training workshops is examining the influence of neuroscience on teaching strategies and embedding these approaches within the curriculum, lesson planning, and daily methodology. The Hub’s approach is grounded in evidence-based practices that adopt insights from brain research to enhance teaching methods. Teachers learn how to apply principles of neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to reorganise itself by forming new neural connections, which is transformative in enabling them to create more adaptable and responsive learning environments. Practical applications, discussed during the workshops, include strategies such as different modes of retrieval practice, with their lesson planning for improving memory retention, fostering critical thinking skills, and boosting overall student engagement through activities that stimulate cognitive development. Emotion regulation, metacognitive and self-regulated learning strategies are integrated into daily teaching routines, promoting both cognitive and emotional intelligence, as well as a growth mindset, among students. By incorporating these strategies into their pedagogy, teachers not only help students manage their emotions but also support their development of metacognitive and self-regulated learning skills. When students can manage their emotions, they are better equipped to monitor and adjust their cognitive strategies, leading to improved focus and more effective engagement with learning activities. Self-regulated learning further enhances this by empowering students to set goals, develop strategies, and self-assess their progress, all while managing emotional responses that might otherwise hinder their learning.

Emotion regulation, metacognitive and self-regulated learning strategies are integrated into daily teaching routines, promoting both cognitive and emotional intelligence, as well as a growth mindset, among students. By incorporating these strategies into their pedagogy, teachers not only help students manage their emotions but also support their development of metacognitive and self-regulated learning skills. When students can manage their emotions, they are better equipped to monitor and adjust their cognitive strategies, leading to improved focus and more effective engagement with learning activities. Self-regulated learning further enhances this by empowering students to set goals, develop strategies, and self-assess their progress, all while managing emotional responses that might otherwise hinder their learning. During the workshops, I emphasise the crucial role of presenting relevant content and introducing novelty to enhance motivation and engagement, as well as evoking emotions in teaching to improve the retention of information and skills. By adopting cognitive strategies that incorporate emotional engagement, teachers can help students not only remember content more effectively but also develop the self-awareness and self-regulation skills necessary for lifelong learning. This integrated approach ensures that students are not only managing their emotions but also applying metacognitive and self-regulation strategies to achieve more profound and sustained learning outcomes.

During the workshops, I emphasise the crucial role of presenting relevant content and introducing novelty to enhance motivation and engagement, as well as evoking emotions in teaching to improve the retention of information and skills. By adopting cognitive strategies that incorporate emotional engagement, teachers can help students not only remember content more effectively but also develop the self-awareness and self-regulation skills necessary for lifelong learning. This integrated approach ensures that students are not only managing their emotions but also applying metacognitive and self-regulation strategies to achieve more profound and sustained learning outcomes.

Educational Neuroscience focuses on creating awareness of evidence-based approaches, necessitating a change in mindset. This shift fosters engaging and thoughtful discussions, making it a fulfilling experience and a pleasure to positively impact teaching approaches. The insightful questions posed by teachers during these workshops reflect their active engagement and critical reflection on their teaching practices. These interactions highlight the success of the various workshops in promoting a deeper understanding of how neuroscience can inform and improve educational practices. Engaging with experienced educators facilitates a rich exchange of ideas, enhancing the training’s effectiveness and providing newly qualified teachers with new strategies and teaching approaches.

Educational Neuroscience focuses on creating awareness of evidence-based approaches, necessitating a change in mindset. This shift fosters engaging and thoughtful discussions, making it a fulfilling experience and a pleasure to positively impact teaching approaches. The insightful questions posed by teachers during these workshops reflect their active engagement and critical reflection on their teaching practices. These interactions highlight the success of the various workshops in promoting a deeper understanding of how neuroscience can inform and improve educational practices. Engaging with experienced educators facilitates a rich exchange of ideas, enhancing the training’s effectiveness and providing newly qualified teachers with new strategies and teaching approaches.