Last week, The Times (@nicolawoolcock) reported a complaint by journalist Toby Young (@toadmeister) that he had been censored for writing that intelligence was largely genetic. What point was Toby Young trying to make by referring to genetic evidence and why was it censored?

According to the Times, Young’s blog argued that IQ is a strong predictor of how children perform in school exams; that schools are largely unsuccessful in raising the IQs of pupils; and that ‘intelligence is a highly heritable characteristic, which is to say that more than half of the variance in IQ at a population level is due to genetic differences’. The context of Young’s article was how he had moderated his early view about the transformative impact that good schools can have, based in part on learning about the greater contribution of genetics to variation in IQ.

There was a negative response to the blog on social media, including that it ‘had deeply nasty connotations’. Teach First (@TeachFirst ), a teacher training organisation, took down the blog, saying the article ‘was against what we believe in’.

Why is genetic data controversial in education?

Genetics is controversial in education because is it sometimes used to support arguments of determinism. In the deterministic narrative, schools have limited influence on children’s academic achievement in the face of more powerful forces, be it genetic variation or socio-economic status. Genetics additionally has negative historical associations with discrimination on the basis of race.

Was the scientific data interpreted correctly?

A recent meta-analysis of 42 datasets involving over 600,000 participants found consistent evidence for beneficial effects of education on cognitive abilities. The effect of schooling was a gain of approximately 1 to 5 IQ points for each additional year of education. Schooling therefore does have a small but measurable effect on intelligence. It is likely smaller than the effect of genetics and of socioeconomic status on IQ.

Importantly, however, genetic effects are not deterministic. If the environment is changed, the genetic effect may disappear. For example, despite the high ‘heritability’ of intelligence often reported in scientific studies, this genetic effect is reduced or eliminated under conditions of socioeconomic privation. When a poor educational environment holds children back, genetics effects can reduce: a study examining reading found reduced genetic effects on reading skills when teaching was poor.

Most of the evidence on genetic effects (‘intelligence is 50% inherited’ and so forth) concerns the differences between people. It does not focus on the absolute level that everyone is performing at (that is, the way people are similar). It is possible for the environment to improve everyone’s intelligence, even while the differences between them are for mainly genetic reasons. Therefore, genetic studies reporting heritability only give part of the picture.

This is relevant because national educational policy is often about changing the conditions for the whole population, (hopefully) raising the education level for all. To take a hypothetical example, the government might decree that schools spend double the amount of time teaching maths. The result would be that all children in the country would get better at maths (though perhaps worse at the topics they have less time for). Those at the top of the maths class might still be near the top, those at the bottom near bottom, perhaps for genetic reasons. The heritability of maths skills could stay the same, even though everyone had improved.

Studies focusing on genetic contributions to education are therefore mainly important for the question of gaps between children, and policy ambitions to narrow gaps. The debate considers the genetic and environmental causes of gaps. These gaps might not primarily stem from variation in school quality, which is the focus of Young’s blog. Indeed, when schools are very good, and in a society with low inequality, any remaining gaps would come from genetic differences (or ‘talent’). If we were to achieve the goal of perfect schools and equal societies, this would eliminate at least half the gaps in educational achievement between children. In that sense, data showing increasing heritability of educational achievement would be an index of progress on those goals (see Asbury and Plomin’s recent book ‘G is for Genes’ for more on this).

However, we should remember that education isn’t about populations, it is about individual children. None of the findings on genetics contradicts the fact that any individual can get better at any skill by working harder at it, irrespective of their genetic make up.

How can genetics benefit education?

Right now, the main message from genetics is that not all differences between children in educational outcomes are environmental.

In the future, based on progress in ‘precision’ medicine, the ultimate promise held out by the application of genetics to education is that we will be able to identify the optimal environments to maximise the genetic potential of each child – to realise their talent. This is a long way off. It requires identifying the biological basis of learning, no mean feat. And there are broader ethical issues to consider about genotyping one’s child and handing over the data to their school. But the promise shows the direction of travel: far from arguing for determinism, genetics is about identifying the best environment for individuals to thrive in.

Before then, as a society, we need to make progress on deciding how we feel about differences between children (in contrast to how well all children are performing). It may be that maximising every child’s (genetic) potential does not narrow the gaps between them. When education empowers every child to reach for the stars, we may have to accept that it is different stars the children are aiming at.

For more information

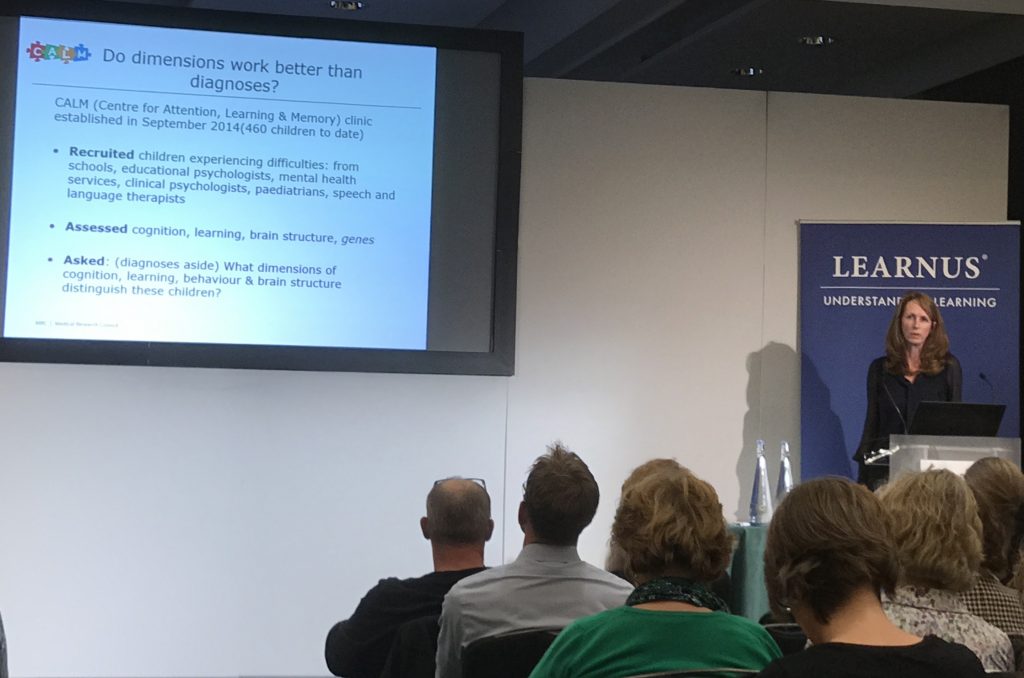

Here is a recent article giving an overview of the use of genetics in education. Here is a video that gives an introduction to the field: Professor Michael Thomas “Genetics and Education” from Learnus – Understanding Learning on Vimeo.