In today’s excerpt from our resource How the brain works, we must come to terms with a rather humbling revelation. We like to believe we are rather clever. If we were asked, we might say our brains are so big and complex because that’s what it takes to create our wonderful, deep, imaginative thoughts. By contrast, reaching out to pick up a cup of coffee and bringing it to our mouth without spilling it isn’t something we’d typically boast about. Well it might be time for a rethink. Grab yourself a cuppa (careful, now) and read on…

Why do you need a brain? Not all organisms have brains. Jellyfish don’t have brains. They do all right, floating about.

Why do you need a brain? Not all organisms have brains. Jellyfish don’t have brains. They do all right, floating about.

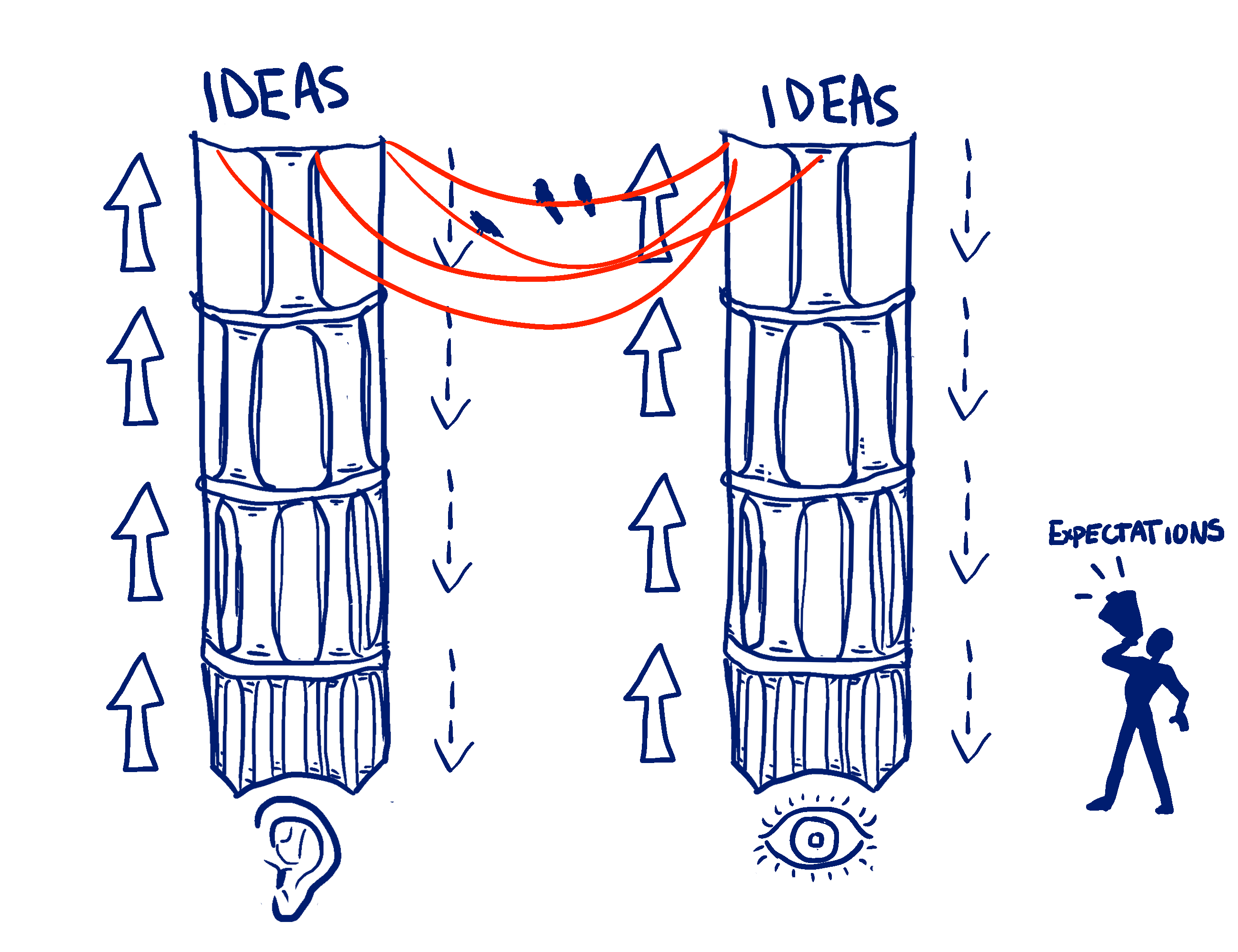

The main reason for having a brain is to coordinate movement. Sight, sound, and other sensory information is brought together; muscles are controlled to produce coordinated movements of the body in response to perception, to achieve the goals of the organism (e.g., eating, not getting eaten).

Trees don’t move and they don’t have brains

Organisms that don’t move don’t need centralised coordination of information. Trees don’t move and they have no brains, not even a nervous system. Jellyfish float, gently swim, and stay upright waiting for prey to hit their tentacles. They have a different type of nervous system for this less demanding repertoire, with separate sets of neurons to synchronise muscle actions in different parts of their bodies. There is no integration in a single central brain.

Sometimes, your spine will do the thinking for you

Even humans don’t always need their brains to move. Sometimes, your spine will do the thinking for you. Touch something hot, and in half a second, you will snatch your hand away. Temperature and danger receptors in the skin have rapidly signalled to the spine,  where local neurons have already decided to trigger the withdrawal reflex, and the arm muscles spring into action. Quick, withdraw your hand! It is, as they would say these days, a real no-brainer. But anything beyond a reflex movement is going to involve the brain.

where local neurons have already decided to trigger the withdrawal reflex, and the arm muscles spring into action. Quick, withdraw your hand! It is, as they would say these days, a real no-brainer. But anything beyond a reflex movement is going to involve the brain.

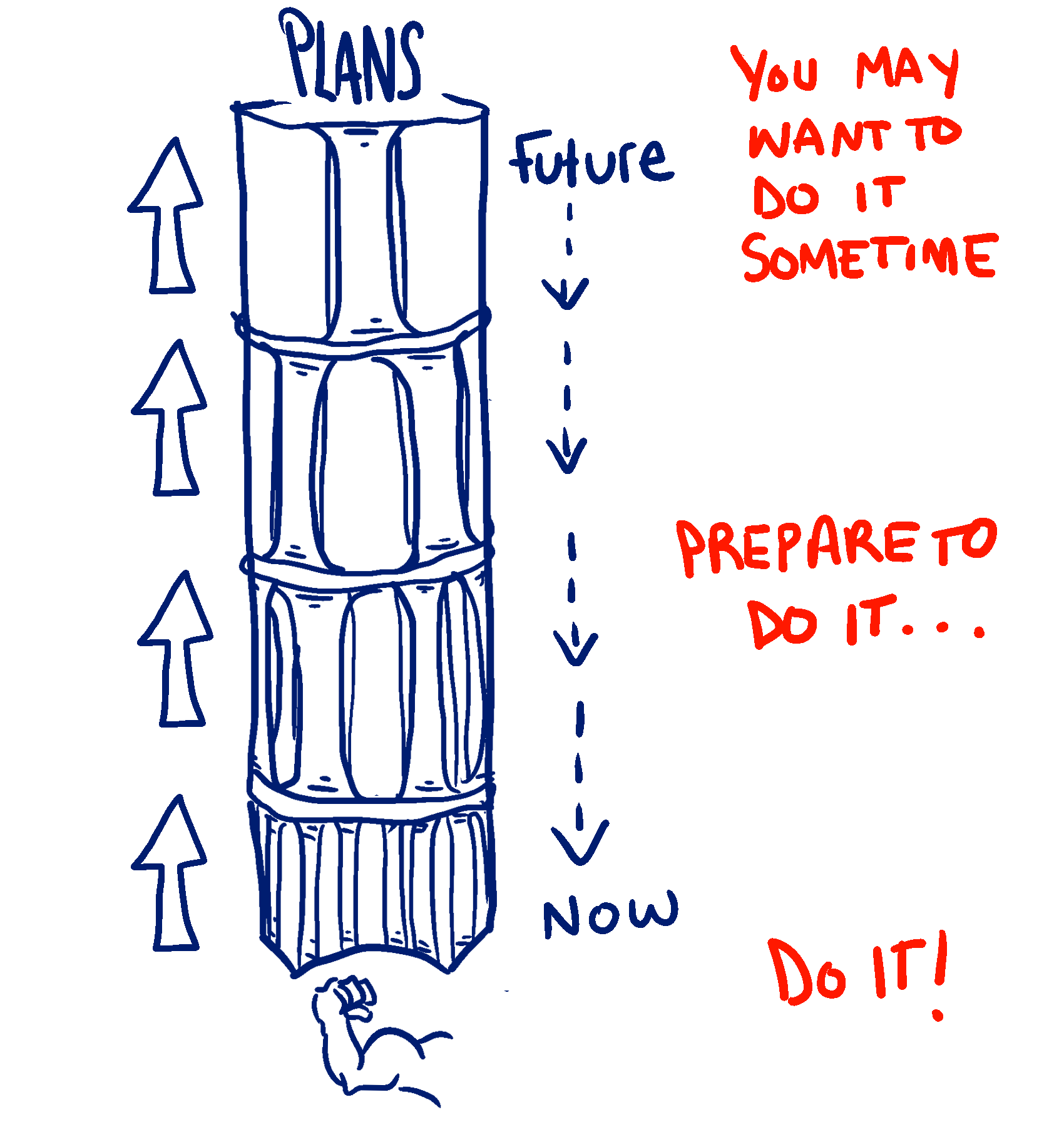

At the other end of the scale, human actions can be vastly subtle and sophisticated, aimed towards long-range goals. Studying for a university degree, for example. But it is worth remembering the primary design influence of the brain: make the right movement.

This influence is still discernible in our ‘high-level’ cognitive skills. Take attention. We focus attention on particular objects in our visual field or on particular sounds around us. The ‘attention network’ in the brain involves the circuits of the particular sense (sight, hearing) and two other regions – a system that processes space and a region that controls eye-movements. In the brain, attention isn’t some abstract part of thought: it is about orienting to objects in space and preparing to make the right movement – including movement of the eyes to look to that region of space to get more information. While ‘paying attention’ in the classroom may be held to be a high-level cognitive skill, inside the brain it is about planning for the right movement.

Hang on a minute, what’s this other bit?

The cerebellum! There’s, like, this whole extra ‘mini’ brain at the back, like a petite cauliflower. And you know what? The cerebellum is so densely packed with neurons, it contains around 80% of all the neurons in the brain. What does it do? Is this where all my brilliant thoughts happen?

The cerebellum! There’s, like, this whole extra ‘mini’ brain at the back, like a petite cauliflower. And you know what? The cerebellum is so densely packed with neurons, it contains around 80% of all the neurons in the brain. What does it do? Is this where all my brilliant thoughts happen?

Well… No. The cerebellum is also all about movement. It is dedicated to the job of coordinating movement and sensation. It needs to make everything hang together, to make it run smoothly and automatically. Because, you know, you may have decided you’re thirsty, and you may want to reach out for that glass of water next to you, but actually your body is already busy. There are muscles holding your posture, keeping you balanced, holding your head up. And if you are going to reach out your arm, a limb is heavy, it’s going to change your centre of gravity. You don’t want to topple over, so lean back a bit, adjust, subtly, unconsciously. A reach of the arm needs to be fitted in with everything else, so that overall movement and posture is smooth, so it all flows together. This takes a lot of integration and monitoring of sensory input and adjusting of motor output. Some heavy-duty number crunching, requiring a lot of neurons and connections. It’s a job for a specialist.

‘When your coffee cup doesn’t quite reach your lips and you spill your coffee down your front . . . only then do you notice what the cerebellum has been up to’

Yet when everything is running smoothly, you don’t notice the cerebellum is there. Only when things go wrong – when your coffee cup doesn’t quite reach your lips and you spill the coffee down your front; when you step off a pavement and misjudge the height of the curb, landing heavily and jarringly – only then do you notice everything the cerebellum has been up to.

It’s keen to take on more work, too. As practised actions become less voluntary and more automatic, the cerebellum takes over from cortical commands to deliver movements swiftly and smoothly.

The cerebellum doesn’t just contribute to movements, but also to thought. Instead of movement, cortex can manipulate images or ideas. When these objects are repeatedly manipulated in the mind, the cerebellum can help make their manipulation smooth and automatic. Here’s some single digit numbers. Six. Eight. Add them together. Adults have years of experience adding single digit numbers. Up pops the answer, 14, smooth as you like, no thinking required, cruise control.

So our brilliant brains are mostly designed for movement. Now that you’ve got your head around that, in our next installment we’ll take a look at how the layers of the brain are organised and start to get an idea of how the whole set up works together.

So our brilliant brains are mostly designed for movement. Now that you’ve got your head around that, in our next installment we’ll take a look at how the layers of the brain are organised and start to get an idea of how the whole set up works together.

If you prefer bingeing and can’t wait, you can leap ahead here

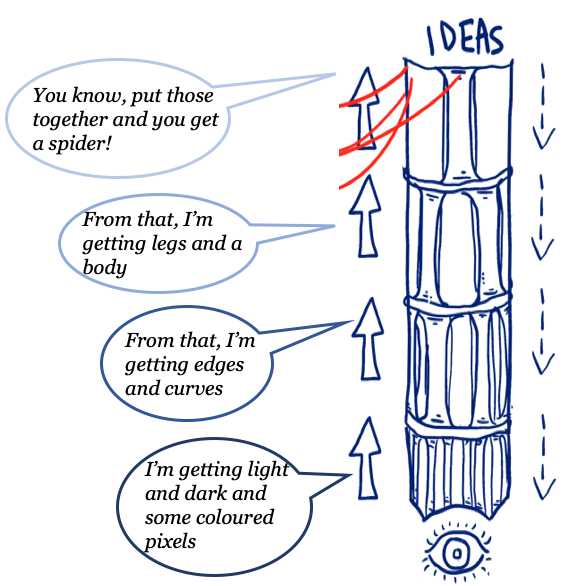

spider, cold cognition recognises the visual pattern, hot cognition gets worried, the body is informed that its heart should race in preparation for fight-or-flight action, and cold cognition prepares the instructions to jump. The layers work together as an integrated whole.

spider, cold cognition recognises the visual pattern, hot cognition gets worried, the body is informed that its heart should race in preparation for fight-or-flight action, and cold cognition prepares the instructions to jump. The layers work together as an integrated whole.

patterns.

patterns.

So, the visual system has been designed to recognise objects from whatever viewpoint: a coffee cup is a coffee cup if seen from the left, the right, or upside down. But in English, we asked children to learn that p, q, b, and d are all different letters, corresponding to different speech sounds. To the young child’s visual system, these all look like the same object (a round bit with a tail) viewed from different angles. It takes months, maybe years of learning to overcome the brain’s preference to interpret what it sees in terms of movable objects, and this is why children learning to read in English often mix up their b’s and d’s, and their 6’s and 9’s.

So, the visual system has been designed to recognise objects from whatever viewpoint: a coffee cup is a coffee cup if seen from the left, the right, or upside down. But in English, we asked children to learn that p, q, b, and d are all different letters, corresponding to different speech sounds. To the young child’s visual system, these all look like the same object (a round bit with a tail) viewed from different angles. It takes months, maybe years of learning to overcome the brain’s preference to interpret what it sees in terms of movable objects, and this is why children learning to read in English often mix up their b’s and d’s, and their 6’s and 9’s.