The CEN has published a new paper in the journal Mind Brain and Education entitled Evidence, policy, education, and neuroscience – state of play of play in the UK, which gives an overview of translational educational neuroscience in the United Kingdom.

We consider the state of translation, describing respectively the state of the dialogue between researchers and educators, the state of evaluation of approaches to improve educational outcomes, and the state of innovation in research translation.

We consider the teacher perspective: what do UK teachers think about educational neuroscience and its potential for informing classroom practice? And how do ideas about pedagogical approaches feature amongst their everyday concerns? We describe the results of a recent survey from a representative sample of over 1000 UK teachers, and a case study of a UK high school teacher who employs educational neuroscience in his practice and what this entails.

We consider the policy perspective and assess the recent move by the UK government to introduce knowledge of cognitive science into initial and early-career teacher training.

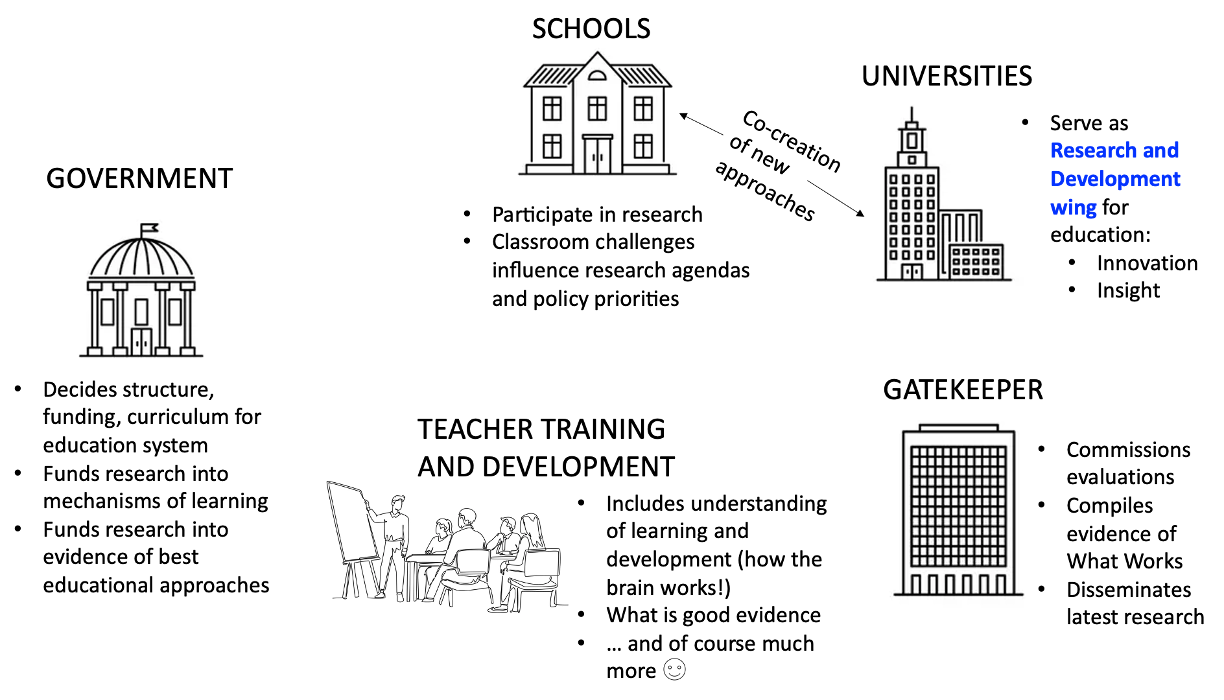

Finally we propose an idealised way that schools, universities, ‘what-works’ clearing houses, teacher training and continuous professional development, and government might interact to support educational innovation. Educational neuroscience feeds into the research and development wing of education. Here’s a picture.

Here are highlights from the paper:

What is already known about this topic?

- Suboptimal dialogue between researchers and practitioners hampers educational neuroscience.

- Randomised controlled trials are a preferred form of evaluation to build an evidence-base for education.

- Teachers’ attitudes to educational neuroscience and its incorporation into teacher training are key aspects of translation.

What does this paper add and how?

- Educational neuroscience can be viewed as a Research and Development (R&D) wing of education, but countries differ in their progress towards this destination.

- A representative UK survey of over 1000 teachers suggested they are open to educational neuroscience but workload and funding are more pressing priorities.

- RCTs yield small effect sizes for single educational interventions but insights into cause, while child-centred approaches yield bigger effects but less insight into why they work.

What are the implications for practice and/or policy?

- A more systematic approach to translation is required to ensure even coverage, and a science of teaching is needed to accompany a science of learning.

- There is insufficient investment in infrastructure for translation to support innovation in education; we need transdisciplinary educational innovation hubs.

- Dialogues between researchers and practitioners need to focus on implementation of educational neuroscience insights in the classroom.

Read the full article at: https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12423

And for those who want more, here’s the Supplementary material, including an interview with Learnus’s Jeremy Dudman-Jones: Supplementary material for Thomas-et-al-2024