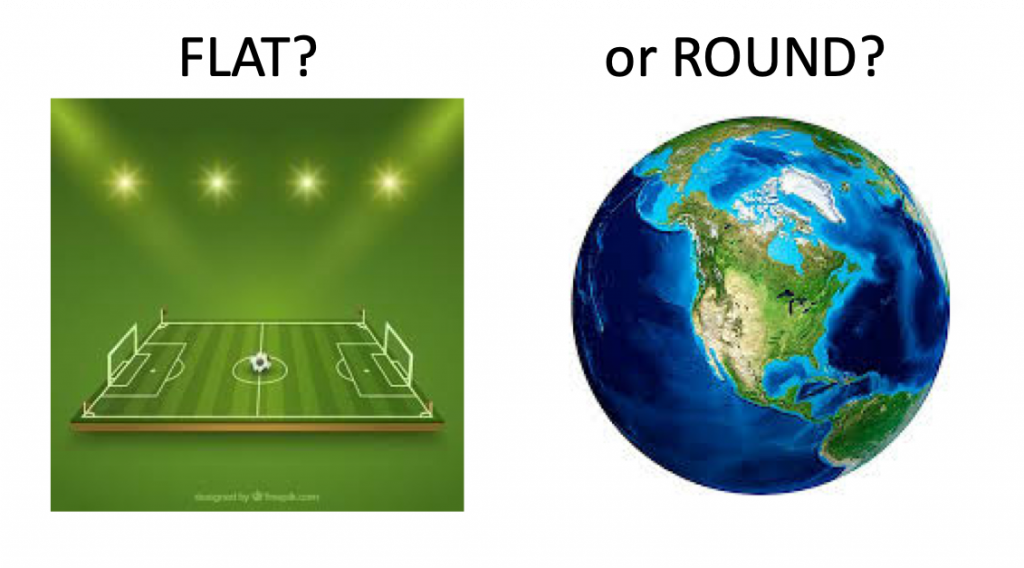

How do kids learn in school that the world is round, when they’ve spent several years playing football on pitches that seem flat? And when they’ve successfully learned the world is round, they still need to carry on playing football as if it were flat.

Funded by the Education Endowment Foundation and the Wellcome Trust, the CEN, in partnership with Learnus, has spent several years developing a computer-based learning activity to help kids learn these sorts of counter-intuitive concepts in science. The activity, called Stop and Think, also extended to mathematics, where a key skill is to stop previous knowledge interfering with new learning. For example, when kids have learned that 5 is bigger than 4, then they need to learn that 1/5 is smaller than 1/4, and -5 is also smaller than -4.

For both science and mathematics, the key target of the computer-based learning activity is to improve what are known as ‘inhibitory control skills’, the ability to suppress knowledge or expectations not relevant to the current situation (see a similar paper discussing these skills in the context of helping kids to stop making repetitive mistakes).

The new learning activity was evaluated in a large-scale randomised control trial, carried out in 89 schools around the country, with some 7,000 8- and 10-year-old children taking part. Children replaced 15 minutes of science or mathematics lessons with the Stop and Think learning activity three times a week, during a regular 10-week term.

Pupils who participated in the programme made the equivalent of +1 additional month’s progress in maths and +2 additional months’ progress in science, on average, compared to children in the lessons-as-usual control group. The cost of using ‘Stop and Think’ is very low and is estimated to be a little over £5 per child over a three-year period. The full report of the randomised control trial from the Education Endowment Foundation can be found here.

When interviewed, a majority of teachers felt that Stop and Think had a positive impact on the mathematical and science abilities of the pupils in their class.

One teacher said: “It allowed me to develop my understanding of how the children in my class learn and to analyse what they know, how clearly they understand concepts and to identify misconceptions that some/most or all children in my class have.”

Another said: “It gave me an insight into how children’s ideas can change when given thinking time and how they are able to reason as to why something is right or wrong.”

In response to the report, Michael Thomas, Director of the CEN, said: “I am really excited about these findings. They show both the viability and value of using new insights from neuroscience to produce low-cost teaching techniques that can improve educational outcomes. Throughout this project, we have been energised by working with teachers to create and improve the learning activities that will allow neuroscience insights to benefit children in the classroom.”