by Jessica Massonnié – https://sites.google.com/site/jessicamassonnie/

Between the 4thand 6thof June, The Wellcome Trust hosted the EARLI SIG22 conference on Neuroscience and Education, organised by Lia Commissar and Annie Brookman-Byrne.

Over two and a half days, various forums and opportunities were provided for teachers and researchers to communicate their work, reflect on their practice, and push the field forward. It is hard to summarise such a dynamic conference in a few words without going into over-heard generalisations, so here are some key moments. The full program as well as the list of attendees is available here.

The keynote talks reflected the interdisciplinarity and diversity of the topics addressed throughout the conference. Heidi Johansen-Berg talked about one of the neuroscience in education projects funded by the Wellcome Trust and Education Endowment Fund – studying the effect of physical activity on the brain and cognition. She also highlighted challenges the team have faced during the process of planning, piloting, and carrying out the study. Nadine Gaab, who develops models to understand the development of the reading brain, demonstrated how neuroscience can be used to inform and develop a reading skills screening tool enabling earlier intervention for children. Robert Plomin gave an interesting update of how the field of genetics has progressed, and how a genetic approach could be used to understand behaviour.

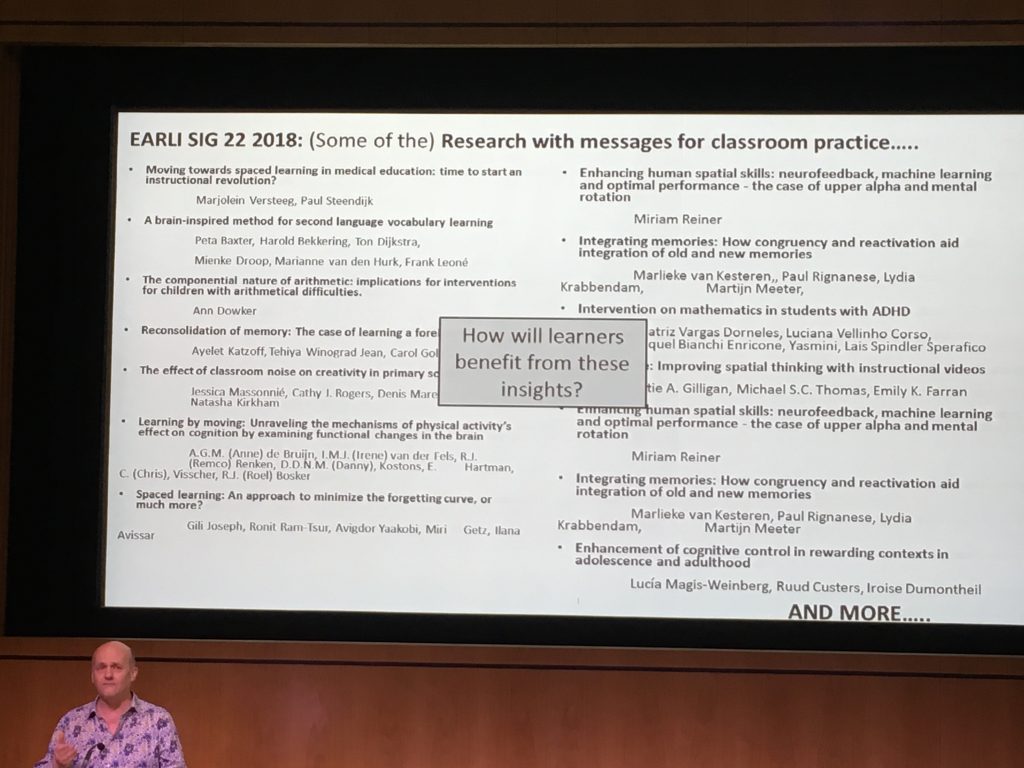

One key line of thought however was to further the collaboration between University research and educational practice. Paul Howard-Jones presented a MOOC, the Science of Learning, aiming to introduce key concepts about cognitive science to teachers. Creating such a platform raises several challenges, such as the understanding of teachers’ needs, the awareness of official guidelines and curriculum, as well as the need to find a compromise between the always evolving and controversial research findings and the delimitation of useful and consensual concepts. This session also highlighted the importance of incorporating the science of learning into initial teacher education, so that new teachers can further understand “why” things may (or may not) be effective for learning.

Slide from Paul Howard-Jones, giving examples of academic papers which have messages for classroom practice.

Echoing his talk, a symposium was focused on how to make science accessible to the public, teachers and policy makers. Yana Weinstein and Megan Sumeracki from the Learning Scientists, Steve Cross, founder of the comedy network Bright Club, as well as Ben Bleasdale, policy advisor from Wellcome, provided some inspiring advice to remain flexible and creative in the dissemination process. Youtube videos, podcasts or stand-up comedy can all help to reach broader audiences and help researchers to reflect on their work by avoiding jargon and thinking about practical applications. Key messages here included being clear about who the audience is that you are aiming to reach, and ensure you plan opportunities that suit that audience (rather than suiting the researcher).

From left to right: Yana Weinstein, Megan Sumeracki, Steve Cross, and Ben Bleasdale

As dissemination and educational applications should be more than a “potential” or “desirable” by-product, a second symposium presented teacher-led research. The booklet “Evidence that counts: 12 teacher-led randomized controlled trials andother styles of experimental research”, edited by the Education Endowment Trust, provides concrete examples of such initiatives. One advantage of teachers carrying out research in their own setting is that it empowers them to design specific research that’s relevant to them. It’s important to remember that there is no “1 size fits all” in education, and teachers should feel empowered to try things out, evaluate, and make changes as appropriate.

From left to right: Richard Churches, Sharon Baker, Charlotte Hindley, Daria Makarova, and Glenn Whitman

Discussions about how to move the field forward culminated on the third day of the conference, offering attendees the opportunity to create group discussions on their topic of interest. The open space sessions fostered the creation of partnerships and the elaboration of concrete action points. Some specific research topics, such as motivation, sleep, or inhibition, were addressed. Discussions about the process of connecting researchers and teachers were also brought to the table / floor. Among others: Cognitive neuroscience into initial teacher education; the creation of a database for researchers and schools who want to work with each other; and ways to measure the effects of teacher neuroscience knowledge on their practice.

In sum, the engaging mix of posters, oral presentations, and discussions means that this conference will remain very memorable, but will also hopefully lead to concrete actions for the future, closer collaboration, and greater understanding about the role of educational neuroscience in teaching and learning.