In this blog, CEN member Mahi Elgamal takes a deep dive into the science of homework: what does the evidence tell us about its effectiveness?

Here’s the take-home:

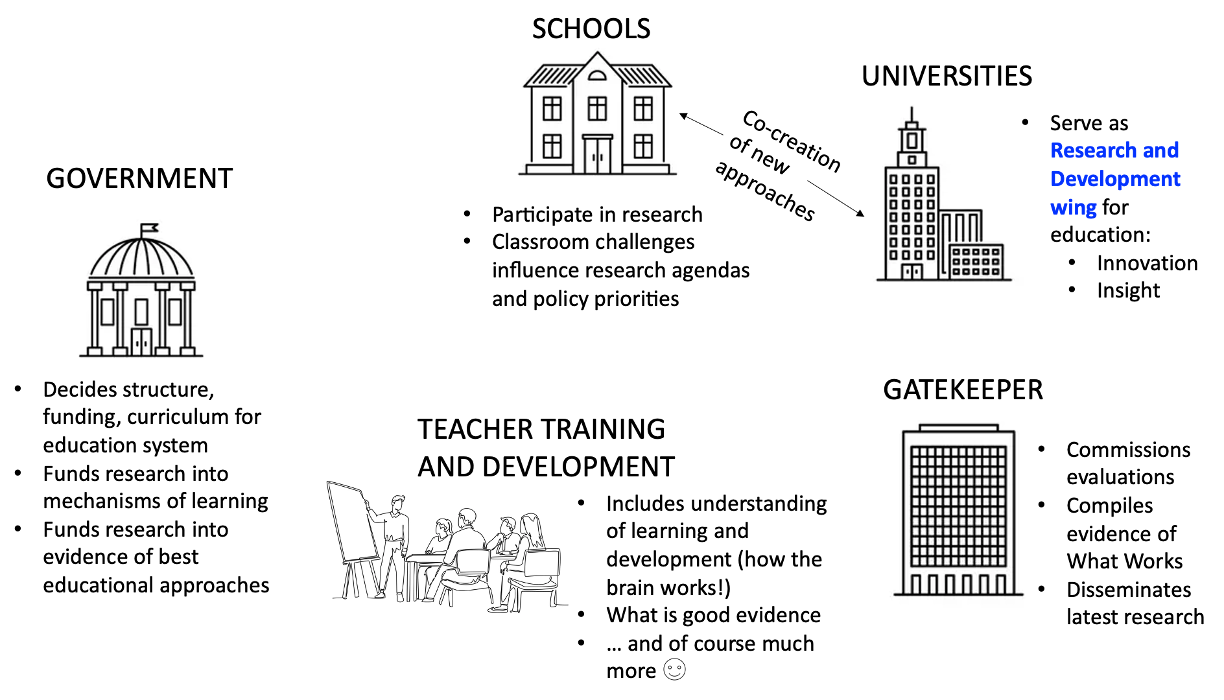

Homework is not legally required in the UK, and neither the UK Department for Education nor the regulatory body Ofsted mandates it. However, many schools still assign homework, starting as early as reception class. Advocates argue that homework helps reinforce learning, promotes independence, develops life skills, and leads to better academic outcomes. Schools typically outline their homework policies in handbooks or on websites.

This article explores how homework supports learning, emphasising retrieval practice (recalling information without notes) and spacing (revisiting material over time) as the most effective strategies. These methods improve long-term retention and are more beneficial than passive techniques like rereading.

Additionally, the effectiveness of homework varies by age. For middle and high school students, it correlates with higher academic achievement, while its benefits for younger children are less clear.

For the full story, read on!

Although in the UK, homework is not compulsory by law, and neither the Department for Education (DfE) nor Ofsted requires schools to assign homework, many schools do set students homework from as young as reception class onwards. Some argue homework is beneficial to help reinforce learning, promote student independence, develop key life skills, and foster stronger academic outcomes. Many schools will set their expectations around homework with parents and students on their website or school handbooks and many schools will ask parents to sign the homework record. As such, parents might wonder: “when is a good time for homework” and “how can I get the most of my child’s homework?”

How does homework help my child’s learning?

Many parents, locked in nightly struggles over homework, may wonder whether and how these tasks benefit their children’s learning. Before discussing the best approach to homework, it is worth first asking: What is homework really meant to achieve?

Researchers have identified effective strategies for independent learning, particularly when applied to homework. Among these, “retrieval practice” and “spacing” stand out with the strongest evidence of effectiveness [1] [2]. Retrieval practice—recalling previously learned information—enhances long-term learning and memory [2].

In the same way, spacing, which involves revisiting material after some time rather than immediately, reinforces learning by encouraging active recall [2]. A homework task that requires children to answer questions about class material without referring to their notes exemplifies these strategies. Retrieval practice and similar learning strategies outperform passive techniques like rereading or reviewing material when it comes to strengthening knowledge gained in the classroom [2]. Homework can be seen as a great opportunity to put these strategies into practice and help foster the development of autonomous and self-regulated learning habits.

Homework across ages: Does it work the same for all children?

The effectiveness of homework can vary by age. For middle and high school students, it is associated with higher standardised scores in tests of academic achievement, while the benefits for younger children are less clear [3]. According to charity the Education Endowment Foundation, homework in primary schools tends to have a smaller average impact and remains under-researched compared to secondary education.

“Studies in secondary schools show greater impact of homework (+5 months additional progress) than in primary schools (+3 months)” – Education Endowment Foundation

Why might that be? One possible explanation could be that homework also comes with some non-academic benefits that are not easily measurable for younger children, like developing their sense of responsibility and independent problem-solving skills which might not be immediately reflected in their achievement in particular subject areas [4]. On the other hand, there are valid concerns about young children’s limited capacity to maintain attention on lengthy tasks and to have already developed solid study habits by tuning out distractions in their environment, compared to older children [5].

The “homework gap”: how does it affect children?

Homework can enhance academic growth for many students, but its impact often varies based on individual backgrounds and resources. Depending on how it is designed and supported, homework can either mitigate or widen socioeconomic-linked attainment gaps.

For disadvantaged children, homework can provide an opportunity to reinforce learning, particularly when they lack academic support at home. However, these children often face barriers, such as inadequate study spaces, limited technology access, unstable internet, and minimal parental guidance. These barriers, often referred to as the “homework gap,” highlight how socioeconomic disparities can lead to uneven academic outcomes [6].

In fact, disadvantaged children are far less likely to have quiet workspaces or reliable devices, and they often receive less parental support for completing homework. A Sutton Trust report, based on OECD PISA data, found that only 50% of the most disadvantaged 15-year-olds receive regular homework help from their parents, compared to 68% of their better-off peers [7]. This disparity means that even high-ability children from low-income families miss out on educational opportunities. In contrast, affluent families often have the resources to provide quiet, well-lit spaces, private tutoring, technology, and additional materials, giving their children an advantage [5].

Lower-income children, by comparison, struggle to complete assignments that require costly supplies or heavy parental involvement, amplifying inequities rather than reducing them [5]. This leads us to the next question: should homework be eliminated altogether?

“We should stop giving homework”—is this privilege speaking?

Eliminating or reducing homework could likely widen the achievement gap. Students from higher-income families benefit from various privileges—such as enriched language environments, access to extracurricular activities like tutoring, and cultural experiences—that are often unavailable to lower-income families. For the 4.3 million children in the UK living in poverty, homework is one tool that can help bridge this gap.

“ELIMINATING HOMEWORK MIGHT WIDEN THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP”

To address these disparities, schools can help by assigning homework that does not rely heavily on technology and extensive parental input. Initiatives such as homework clubs can provide structured environments and reliable access to resources [7]. Schools can also offer quiet study areas and workshops to help parents support their children’s learning. By implementing these measures, schools can create more equitable opportunities for disadvantaged children to keep up with their more affluent peers. However, in low socioeconomic schools, some of these measures may be challenging due to limited space and resources.

How can I best help my child with their homework?

Parental involvement in homework is often described as a “double-edged sword”, offering both opportunities and challenges to the parent-child relationship. While it is well-documented that parental engagement can positively influence student outcomes, the quality of support plays an important role in determining its effectiveness, with some difference seen across year groups and subjects [8], [9].

“PARENTS SHOULD GUIDE NOT CONTROL”

One way to scaffold motivation is through autonomy-supportive involvement, where parents guide rather than control—a method widely recognised as the most effective for enhancing achievement, especially in late childhood and adolescence [5], [10], [11]. Autonomy-supportive behaviours include avoiding controlling language and attitudes (such as invasive forms of help and constant monitoring), respecting children’s perspectives, and allowing them enough time to complete tasks independently rather than solving problems for them [12].

Providing structure—for example, helping to set clear goals, expectations, and directions—encourages a sense of internal control over learning and helps maintain feelings of competence [13]. Similarly, offering detailed instructions, action plans, and constructive feedback can further support children’s engagement [14].

This approach encourages children to develop their own schedules and solve problems independently, which nurtures both skill development and a sense of competence, while still being there for help. Controlling approaches, however, may hinder children’s ability to take initiative and reduce their intrinsic motivation and learning engagement [15], [16].

For example, an autonomy-supportive parent may seek the child’s input, try to understand their approach to solving the task, and encourage them to work independently. In contrast, a controlling parent would likely dictate how the homework should be done, offering little to no opportunity for the child to contribute to the conversation [17].

The benefits of autonomy-supportive involvement are twofold. First, it promotes skill development by enabling children to independently navigate challenges, enhancing their problem-solving abilities and self-efficacy [11]. Second, it supports their motivational growth by allowing them to take ownership of their learning, thereby increasing their engagement in academic tasks [16], [10].

A growing body of research suggests that parents adopting an autonomy-supportive approach can lead to improvements in school performance [17]. That is because when parents are overly controlling, children can miss the experience of tackling challenges on their own and may feel deprived of autonomy and sense of agency.

These positive effects of autonomy support begin early and extend into adolescence [18], [16]. Striking the right balance—where parents stepping in as helpful guides rather than taking over completely—allows children to feel capable and in charge of their learning and build not only academic skills but also critical motivational resources for sustained engagement in school [15], [16].

How parental involvement extends beyond grades

Effective parental involvement extends beyond academic outcomes, influencing other aspects of a child’s development, such as motivation, time management, and the ability to self-regulate. It involves modelling, reinforcing, and open dialogue to nurture positive attitudes, behaviours, and active engagement with learning [19].

For example, when parents show positive attitudes toward homework, it reflects in their children’s motivation, mood, and engagement in school learning [3]. It can influence how they allocate their time and effort to homework and develop a sense of personal responsibility for learning and task completion. Excessive demands—whether from parents, children, or teachers—can strain the parent-child relationship and create frustration, especially when a child struggles academically [20].

While it is no surprise that student achievement is often the focus when looking at parental involvement outcomes, it is equally important to consider its wider effects. Effective parental involvement in homework includes a range of learning outcomes that are closely linked to student achievement, such as the development of self-regulation skills and positive attitudes and behaviours towards learning. Although these proximal outcomes might be harder to measure than test scores, they play an important role in how children approach learning tasks and are crucial for their long-term academic and personal success [8].

Establishing study habits early in a child’s life provides a foundation for developing more advanced skills over time, much like scaffolding in construction. Introducing these habits later, such as during middle school or the teenage years, can be more challenging as routines are already well-established, and adolescents are often more influenced by their peers than by adults.

Is there such thing as the perfect time for homework?

While there is some evidence suggesting a morning advantage for cognitively demanding tasks [21], this research typically focuses on tasks conducted in a school setting (e.g., morning versus afternoon classes).

While direct studies on the optimal time of day for out-of-school homework are lacking, existing research suggests that aligning learning activities with a child’s chronotype could enhance cognitive performance [22]. For instance, younger children, particularly in preschool and kindergarten, tend to be more morning-oriented, with a shift toward “eveningness” occurring around puberty or adolescence. Evening-type adolescents, in particular, tend to show improved achievement and motivation in the afternoon compared to the morning, where they experience lower interest and joy in learning. This effect has been consistently observed across various studies [22].

“WHETHER A CHILD DOES THEIR HOMEWORK BEFORE TEA OR AFTER TEA, THE KEY IS A CONSISTENT ROUTINE”

Given these individual differences, some children may benefit from a break right after school to engage in physical activity or have a snack, while others may prefer to begin their homework immediately, taking advantage of the momentum from being in “school mode.”

Regardless of the timing, establishing a consistent routine is necessary. To encourage consistency, Harris Cooper—a leading homework researcher—recommends that younger children complete their homework at the same time every day, whether right after school, just before dinner, or shortly afterward. He also advises avoiding late-night homework sessions, as they may disrupt sleep and reduce productivity.

Quality over quantity of time spent

There is a positive association between time spent on homework and academic achievement [23]. However, how students manage their homework time is just as important as the amount of time spent. Research shows that academic success is closely tied to how much homework students actually complete, especially when they concentrate on finishing assigned tasks rather than just logging hours [24], [25].

“GOOD TIME MANAGEMENT CAN TRANSFORM MORE HOMEWORK INTO BETTER HOMEWORK”

Simply increasing homework time does not necessarily lead to better academic performance, and in some cases, excessive time spent may have a negative impact on achievement [24], [26]. The key lies in how that time is being managed—effective organisation and goal setting can transform “more homework” into “better homework” [24], [25].

Poor time management may diminish homework’s potential benefits [25]. Prioritizing quality and efficiency in homework over simply the length of time spent is important. Children who effectively manage their homework time not only complete more assignments but also achieve higher grades[27], [28].

Good time management goes together with improved behavioural engagement, helping children allocate their time wisely and avoid procrastination [26], [29]. Supporting children with organising and managing their homework time is one of the most reliable ways to improve both completion rates and academic achievement [28]. It also helps them resist the urge to procrastinate and to take on more challenging tasks instead of only opting for easier, more immediate, or pleasurable ones.

How much homework is too much?

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medication or dietary supplements. If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.” – Prof. Harris Cooper, Duke University

We should reassure you that there’s no evidence that too much homework can kill you. Nevertheless, spending an excessive amount of time on homework can lead to mental fatigue, anxiety, and reduced readiness to learn [30]. Once children grasp the homework content, doing more may not be helpful. In fact, the benefits from additional homework may decrease over time, potentially even hitting a plateau [31], [32]. This means that teachers should make sure that homework is manageable and that it encourages critical thinking.

“WHEN IT COMES TO HOMEWORK, HOW IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN HOW MUCH”

For elementary students, more time spent on homework has been linked to lower performance [33]. Middle school students tend to achieve better outcomes with around 90 minutes of homework. Interestingly, those who go over this amount might perform worse than their peers spending less time on assignments [3], [34], [29]. High school students did see improvements with additional homework, but even their progress levelled off after about two hours a day. This could suggest that students who spend longer on homework might also be facing more difficulties with the material [3].

It is worth keeping in mind that excessive homework not only increases cognitive load and tiredness but might also cut down on the time available for other activities that contribute to children’s overall development.

Because the “optimal” homework duration is still uncertain and likely varies by subject age group, and individual needs, more research is needed to explore key factors such as homework duration, feedback practices, and moderating variables like age, gender, and parental involvement.

Some schools follow the “10-minute rule,” which recommends 10 minutes of homework per night in first grade, adding 10 minutes for each subsequent grade [35]. This serves as a rough anchor, but this could still vary based on assignment type and students’ needs—high-interest reading may justify longer homework, while memorisation tasks may require less time. More research is also needed on the differing impacts by subject matter. The takeaway here is that when it comes to homework “how is more important than how much” [29].

Why does homework stress students out?

Negative affect and stress during homework can undermine its benefits, causing students to procrastinate, disengage, or exert minimal effort on assignments [24]. Stress often arises when tasks seem excessively demanding or time-intensive, creating a mismatch between a child’s abilities and the expectations placed on them [36]. This imbalance reduces both the child’s and the parent’s confidence in their capabilities or available resources, further contributing to stress.

There is a direct link between the number of hours devoted to homework and increased stress levels, which is also reflected in physical health concerns [37]. Many children experience low self-efficacy while doing homework [36] and believe it to be irrelevant, a task that must be done, with no room for choice, which makes the situation even more stressful [38].

“HOMEWORK CAN BE TEDIOUS AND MENTALLY TAXING”

However, not all homework is equally stressful. Integrating student choice and relevance, alongside adequate parental support, can help reduce stress levels [36]. Likewise, well-designed homework (e.g., well-selected and cognitively challenging tasks) that aligns with students’ skills and interests can improve self-efficacy and reduce feelings of irrelevance [38].

This highlights the importance of thoughtful task design and a supportive environment to help students manage stress and engage more effectively with homework. It is also important to acknowledge that homework can be tedious and mentally taxing, and there are natural limits to a student’s ability to concentrate.

When homework becomes excessive, it can not only elevate stress but also disrupt sleep, leading to reduced performance in class or tests and ultimately undermining students’ readiness to learn [39]. To ensure homework is both effective and manageable, teachers and school administrators should work together to assign the appropriate amount of homework for each year group [30].

How can the right kind of break help?

Children’s brains, particularly those of younger children, do not yet have the resources for extended periods of focus without breaks [40]. This limitation is linked to the ongoing development of the prefrontal cortex, which is one of the last brain regions to mature [41]. As this region matures, it plays an important role in cognitive functions such as attention and memory. However, this maturation process is gradual, meaning that younger children may struggle to maintain focus for extended periods [41]. When this occurs, children may become restless, distracted, verbally complain, and find it more challenging to retain new information.

“TAKING BREAKS CAN IMPROVE ATTENTION WHICH IS PARTICULARLY EFFECTIVE FOR HOMEWORK”

Young children’s attention is maximised when their task efforts are spaced out. This is consistent with the concept of ‘distributed effort’, which suggests that children learn better when their tasks are broken up, allowing their efforts to be spread across time rather than sustained without rest [40]. Taking breaks before frustration or lack of focus sets in can be beneficial. These breaks can take different forms; for example some research suggests that integrating physical activity, particularly those that are cognitively engaging, helps sustain children’s attention-to-task and processing speed [42]. These breaks have been shown to improve attention and executive functions, which are particularly effective for homework [42], [43].

Some examples from the studies include activities such as instructing children to touch numbers placed on the ground by running through them, as well as tasks involving quick physical responses, like imitating a jump from a horse when hearing the keyword “hurdle.” The nature of these activities can vary depending on factors such as the child’s age, available resources, etc.

So, whether the break is physically vigorous or sedentary, the important factor is that a break—of any form—provides the opportunity for rest and spacing out effort over time [40].

Can a sweet snack boost my child’s focus?

One common question among parents is whether children should eat before or after completing homework and whether certain food, including sugar, can provide a short-term cognitive boost. Research shows that consuming carbohydrates increases blood glucose levels, which in turn helps improve memory and attention [44].

“GO ON, HAVE A SNACK”

For example, when children consumed a sugary snack (containing predominately simple carbohydrates), their performance on a task requiring sustained attention was considerably better than when they had a non-caloric snack [44]. This suggests how even a small, energy-rich snack can help a child stay focused [44].

Importantly, glucose consumption does not appear to lead to hyperactivity, either in typically developing children or those with attention deficit disorder [45]. In fact, a late afternoon energy-rich snack can improve cognitive performance, especially on tasks requiring sustained attention. It can also improve spatial memory, as shown by better performance on map learning and recall tasks [46]. However, factors like the time of day, a child’s age, the type of task at hand, and whether they have fasted can all influence how a sugary snack affects cognitive performance [44].

So where are we now?

Homework remains as one of the more challenging pedagogical strategies to study. The most reliable research designs–especially those that randomly assign students to either receive homework or not–can only be done at the level of specific subjects. Conducting definitive studies on the long-term effects of homework is nearly impossible. Despite these limitations, most researchers and educators seem to agree that homework does have positive effects.

“RESEARCH ON THE LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF HOMEWORK IS NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE BUT MOST EDUCATORS AGREE IT HAS POSITIVE EFFECTS”

What is now needed is more research focused on how children can make the most of these benefits while minimising potential downsides based on their different backgrounds and the nature of assignments. The key factors are how and when assignments are given. Both the positive and negative effects can vary based on a student’s background and home environment, as well as the type and amount of homework they receive.

The consensus is clear: quality matters more than quantity. Short, well-designed assignments are far more effective than lengthy, poorly constructed ones, which risk undermining learning altogether. Assigning homework that spark a student’s interest and creativity tend to engage them more effectively. However, what constitutes a “quality assignment” can differ based on the subject. For instance, areas like spelling, vocabulary, and foreign language often require practice and memorisation. While these assignments might not seem very exciting, they play a crucial role, nonetheless.

The key for parents, educators, and researchers is to focus on tailoring homework to students’ needs and contexts, ensuring it is purposeful, balanced, and meaningful. By identifying strategies that enhance the positive effects while mitigating the negative ones, homework can become a more effective tool for fostering learning and development.

References

[1] J. Dunlosky, K. A. Rawson, E. J. Marsh, M. J. Nathan, and D. T. Willingham, ‘Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology’, Psychol. Sci. Public Interest, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 4–58, Jan. 2013, doi: 10.1177/1529100612453266.

[2] H. L. I. Roediger and A. C. Butler, ‘The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention’, Trends Cogn. Sci., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 20–27, 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003.

[3] H. Cooper, J. C. Robinson, and E. A. Patall, ‘Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003’, Rev. Educ. Res., vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 1–62, 2006, doi: 10.3102/00346543076001001.

[4] B. J. Zimmerman and A. Kitsantas, ‘Homework practices and academic achievement: The mediating role of self-efficacy and perceived responsibility beliefs’, Contemp. Educ. Psychol., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 397–417, 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.05.003.

[5] H. Cooper and J. C. Valentine, ‘Using research to answer practical questions about homework’, Educ. Psychol., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 143–153, 2001, doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3603_1.

[6] S. L. Hofferth and J. F. Sandberg, ‘How American children spend their time’, J. Marriage Fam., vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 295–308, 2001, doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00295.x.

[7] S. Trust, ‘Homework: Lessons from PISA’. 2017.

[8] E. A. Patall, H. Cooper, and J. C. Robinson, ‘Parent Involvement in Homework: A Research Synthesis’, Rev. Educ. Res., vol. 78, no. 4, pp. 1039–1101, 2008, doi: 10.3102/0034654308325185.

[9] N. E. Hill and D. F. Tyson, ‘Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement’, Dev. Psychol., vol. 45, no. 3, pp. 740–763, 2009, doi: 10.1037/a0015362.

[10] E. M. Pomerantz, E. A. Moorman, and S. D. Litwack, ‘The how, whom, and why of parents’ involvement in children’s academic lives: More is not always better’, Rev. Educ. Res., vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 373–410, 2007, doi: 10.3102/003465430305567.

[11] F. F. Ng, G. A. Kenney-Benson, and E. M. Pomerantz, ‘Children’s achievement moderates the effects of mothers’ use of control and autonomy support’, Child Dev., vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 764–780, 2004, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00705. x.

[12] S. T. Gurland and W. S. Grolnick, ‘Perceived threat, controlling parenting, and children’s achievement orientations’, Motiv. Emot., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 103–121, 2005, doi: 10.1007/s11031-005-7956-2.

[13] E. Skinner, C. Furrer, G. Marchand, and T. Kinderman, ‘Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic?’, J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 100, pp. 765–781, 2008, doi: 10.1037/a0028089.

[14] H. Jang, J. Reeve, and E. L. Deci, ‘Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure’, J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 102, no. 3, pp. 588–600, 2010, doi: 10.1037/a0019682.

[15] E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan, Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Springer Science & Business Media, 1985. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7.

[16] W. S. Grolnick, The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2003.

[17] A. C. Vasquez, E. A. Patall, C. J. Fong, A. S. Corrigan, and L. Pine, ‘Parent Autonomy Support, Academic Achievement, and Psychosocial Functioning: a Meta-analysis of Research’, Educ. Psychol. Rev., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 605–644, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9329-z.

[18] G. S. Ginsburg and P. Bronstein, ‘Family factors related to children’s intrinsic/extrinsic motivational orientation and academic performance’, Child Dev., vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 1461–1474, 1993, doi: 10.2307/1131546.

[19] K. V. Hoover-Dempsey and H. M. Sandler, ‘Parental involvement in children’s education: Why does it make a difference?’, Teach. Coll. Rec., vol. 97, no. 2, pp. 310–331, 1995, doi: 10.1177/016146819509700202.

[20] M. Holland et al., ‘Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact’, Child Youth Care Forum, vol. 50, pp. 631–651, 2021, doi: 10.1007/s10566-021-096.

[21] N. G. Pope, ‘How the Time of Day Affects Productivity: Evidence from School Schedules’, Rev. Econ. Stat., vol. 98, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2016, doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00525.

[22] H. Itzek-Greulich, C. Randler, and C. Vollmer, ‘The interaction of chronotype and time of day in a science course: Adolescent evening types learn more and are more motivated in the afternoon’, Learn. Individ. Differ., vol. 51, pp. 189–198, Oct. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2016.09.013.

[23] M. Holmes and P. Croll, ‘Time spent on homework and academic achievement’, Educ. Res., vol. 31, pp. 36–45, 1989, doi: 10.1080/0013188890310104.

[24] U. Trautwein, I. Schnyder, A. Niggli, M. Neumann, and O. Lüdtke, ‘Chameleon effects in homework research: The homework–achievement association depends on the measures used and the level of analysis chosen’, Contemp. Educ. Psychol., vol. 34, pp. 77–88, 2009, doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.09.001.

[25] J. C. Núñez, N. Suárez, P. Rosário, G. Vallejo, A. Valle, and J. L. Epstein, ‘Relationships between perceived parental involvement in homework, student homework behaviors, and academic achievement: differences among elementary, junior high, and high school students’, Metacognition Learn., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 375–406, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1007/s11409-015-9135-5.

[26] S. Dettmers, U. Trautwein, M. Lüdtke, M. Kunter, and J. Baumert, ‘Homework works if homework quality is high: Using multilevel modeling to predict the development of achievement in mathematics’, J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 102, pp. 467–482, 2010, doi: 10.1037/a0018453.

[27] B. J. C. Claessens, W. van Eerde, C. G. Rutte, and R. A. Roe, ‘A review of the time management literature’, Pers. Rev., vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 255–276, 2007, doi: 10.1108/00483480710726136.

[28] J. Xu, ‘Predicting homework time management at the secondary school level: A multilevel analysis’, Learn. Individ. Differ., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 34–39, 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2009.11.001.

[29] R. Fernández-Alonso, J. Suárez-Álvarez, and J. Muñiz, ‘Adolescents’ homework performance in mathematics and science: Personal factors and teaching practices’, J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 107, no. 4, pp. 1075–1085, 2015, doi: 10.1037/edu0000032.

[30] L. Guo et al., ‘The relationship between homework time and academic performance among K-12: A systematic review’, Campbell Syst. Rev., vol. 20, no. 3, p. e1431, 2024, doi: 10.1002/c.

[31] P. L. Ackerman, T. Chamorro-Premuzic, and A. Furnham, ‘Trait complexes and academic achievement: old and new ways of examining personality in educational contexts’, Br. J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 81, no. Pt 1, pp. 27–40, 2011, doi: 10.1348/000709910X522564.

[32] D. Bartelet, J. Ghysels, W. Groot, C. Haelermans, and H. Maassen van den Brink, ‘The differential effect of basic mathematics skills homework via a web‐based intelligent tutoring system across achievement subgroups and mathematics domains: A randomized field experiment’, J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 1–20, 2016, doi: 10.1037/edu0000051.

[33] S. Farrow, P. Tymms, and B. Henderson, ‘Homework and Attainment in Primary Schools’, Br. Educ. Res. J., vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 323–341, 1999.

[34] L. Shumow, Homework and study habits. IAP Information Age Publishing, 2011.

[35] S. Redding, ‘Parents and learning’. UNESCO Publications, 2000.

[36] A. Moè, I. Katz, and M. Alesi, ‘Scaffolding for motivation by parents, and child homework motivations and emotions: Effects of a training programme’, Br. J. Educ. Psychol., vol. 88, pp. 323–344, 2018, doi: 10.1111/bjep.12216.

[37] N. M. Kouzma and G. A. Kennedy, ‘Homework, stress, and mood disturbance in senior high school students’, Psychol. Rep., vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 193–198, 2002, doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.91.1.193.

[38] J. Xu, ‘Purposes for doing homework reported by middle and high school students’, J. Educ. Res., vol. 99, no. 1, pp. 46–55, 2005.

[39] S. C. Yeo, J. Tan, J. C. Lo, M. W. L. Chee, and J. J. Gooley, ‘Associations of time spent on homework or studying with nocturnal sleep behavior and depression symptoms in adolescents from Singapore’, Sleep Health, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 758–766, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.07.007.

[40] A. D. Pellegrini and D. F. Bjorklund, ‘The role of recess in children’s cognitive performance’, Educ. Psychol., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 35–40, Jan. 1997, doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3201_3.

[41] B. J. Casey, J. N. Giedd, and K. M. Thomas, ‘Structural and functional brain development and its relation to cognitive development’, Biol. Psychol., vol. 54, no. 1–3, pp. 241–257, 2000, doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(00)00058-2.

[42] M. Schmidt, V. Benzing, and M. Kamer, ‘Classroom-based physical activity breaks and children’s attention: Cognitive engagement work!’, Front. Psychol., vol. 7, 2016, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01474.

[43] F. Egger, V. Benzing, A. Conzelmann, and M. Schmidt, ‘Boost your brain, while having a break! The effects of long-term cognitively engaging physical activity breaks on children’s executive functions and academic achievement’, PLoS ONE, vol. 14, 2019.

[44] C. Busch, H. Taylor, R. Kanarek, and P. Holcomb, ‘The effects of a confectionery snack on attention in young boys’, Physiol. Behav., vol. 77, pp. 333–340, 2002, doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00882-X.

[45] M. Wolraich, R. Milich, P. Stumbo, and F. Schultz, ‘Effects of sucrose ingestion on the behavior of hyperactive boys’, J. Pediatr., vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 675–682, 1985, doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80102-5.

[46] C. R. Mahoney, H. A. Taylor, and R. B. Kanarek, ‘Effect of an afternoon confectionery snack on cognitive processes critical to learning’, Physiol. Behav., vol. 90, no. 2–3, pp. 344–352, 2007, doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.033.